Abstract

Clinical guidelines recommend the development of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) networks at community, regional and/or national level to ideally offer primary coronary angioplasty, or at least the best available STEMI care to all patients. However, there is a discrepancy between this clinical recommendation and daily practice, with no coordinated care for STEMI patients in many regions of the world. While this can be a consequence of lack of resources, in reality it is more frequently a lack of organisational power. In this paper, the Stent - Save a Life! Initiative (www.stentsavealife.com) proposes a practical methodology to set up a STEMI network effectively in any region of the world with existing resources, and to develop the STEMI network continuously once it has been established.

Introduction

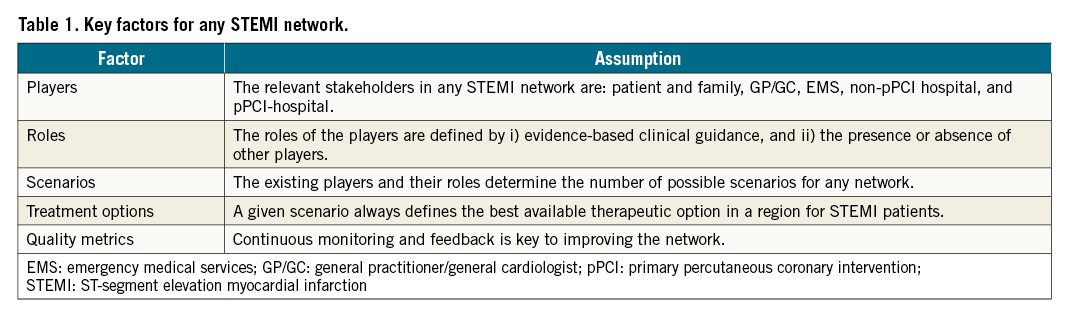

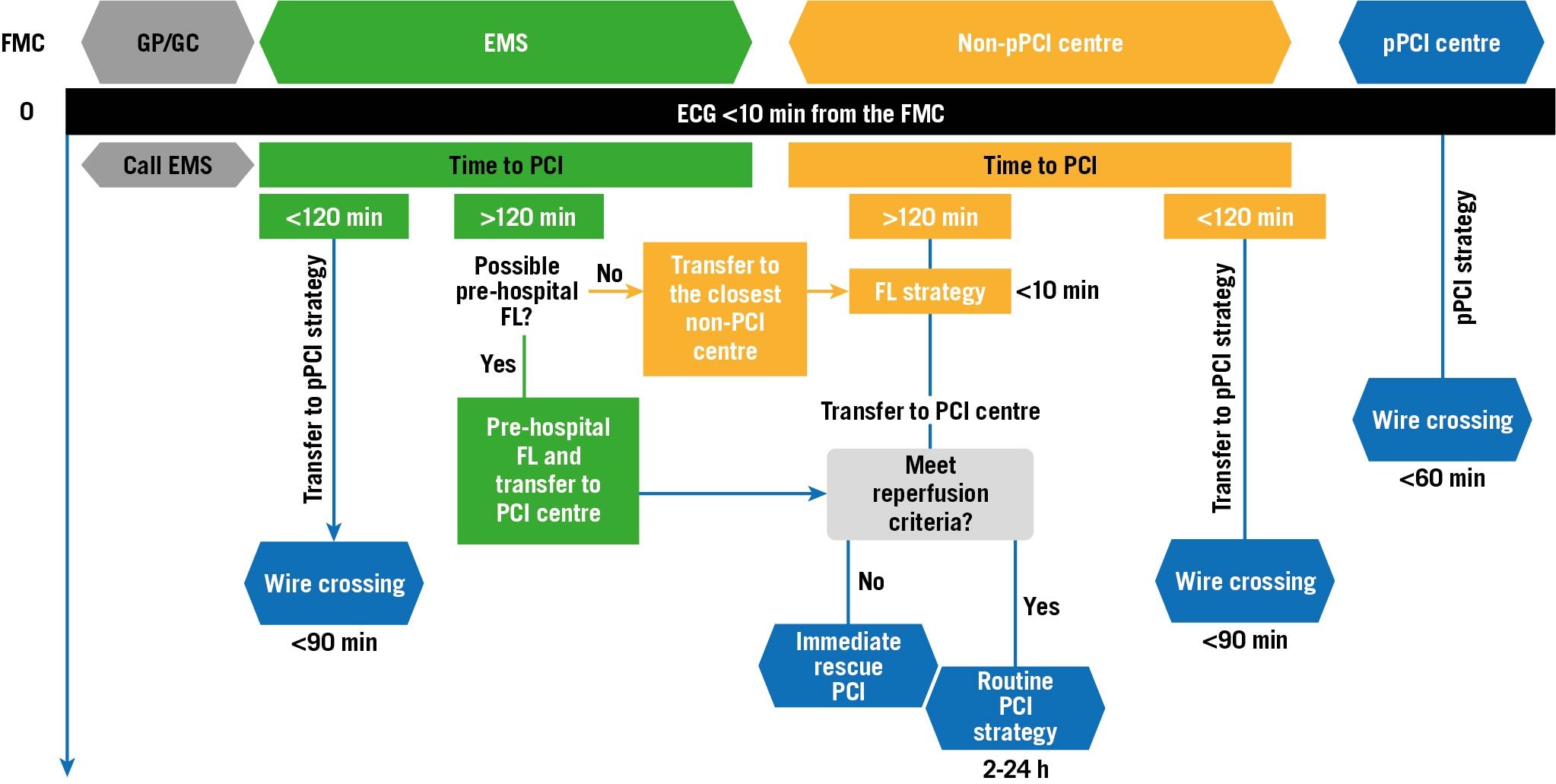

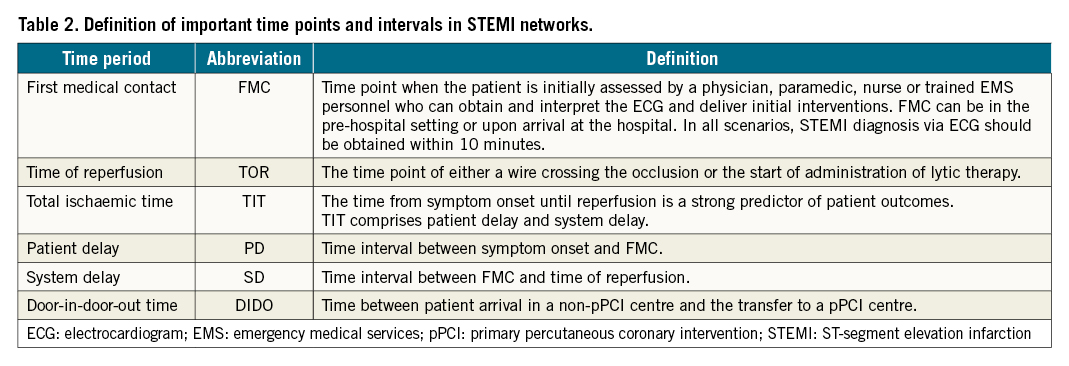

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the preferred reperfusion therapy for patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), as recommended by clinical guidelines1. pPCI is clearly superior to all other treatments investigated to date regarding mortality and morbidity and, in addition, is cost saving for national economies2. All healthcare systems should aim to provide pPCI to all STEMI patients, independent of location, nationality, race, sex or personal wealth. As a first step, available resources should be organised to provide the best available care to all patients and to optimise STEMI management nationwide. To reach this goal, systems of care for STEMI management need to be developed at a community, regional and/or national level345. This document proposes a universal methodology to provide the best available, guideline-adherent care for STEMI patients based on five general assumptions (Table 1).

Review of clinical guidelines

Therapeutic options

Reperfusion of the myocardium by pPCI within 12 hours of symptom onset is the cornerstone of STEMI treatment, followed by a pharmacoinvasive strategy (PI) if pPCI cannot be performed within 120 minutes of diagnosis, or, if the latter is also not available, stand-alone fibrinolysis. In any PI or lysis strategy, patients should be transferred urgently to a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centre after lysis1678.

Choice and timing of the optimal therapy

As a first step, all healthcare systems should develop regional networks of care for STEMI patients to counter regional disparities as much as possible9. Until timely pPCI can be provided to all patients, the preferred reperfusion strategy for each patient will depend on local resources, timing, and the entry point into the network (Figure 1, Table 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Recommended reperfusion strategies according to timing and point of entry to the network. ECG: electrocardiogram; EMS: emergency medical services; FL: fibrinolysis; FMC: first medical contact; GP/GC: general practitioner/general cardiologist; min: minutes; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Characteristics, elements and roles in a STEMI network

Only an effectively organised STEMI network will ensure that all STEMI patients will be optimally treated within the window of opportunity. All resources and processes in a region should be organised to serve this single purpose.

Main characteristics of a STEMI network

- 24/7 treatment service for all STEMI patients

- structured cooperation among all parties involved following standardised protocols

- regular structured meetings and continuous education of all parties involved

- continuous self-assessment and improvement of the network.

Main players in a STEMI network

Patients

Ideally patients should be able to recognise symptoms of myocardial infarction and understand the importance of receiving urgent treatment. They should understand how to activate the emergency medical services (EMS) or otherwise seek immediate medical attention (Supplementary Table 2).

General practitioner/general cardiologist (GP/GC)

GPs/GCs play an important role as first responders to patient consultations. GPs/GCs should be integrated into a STEMI network and should be able to recognise and manage patients with STEMI according to standardised protocols (Supplementary Table 2).

Emergency medical services

EMS are important coordinators of the referral pathway310. Their main actions entail pre-hospital patient management and between-hospital transfers. An EMS should always coordinate its actions with the network and notify the receiving hospital prior to arrival to check capacities and allow preparation. Ideally, all EMS should be centralised and activated through a single and well-publicised dispatch telephone number1 (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2).

Non-pPCI centres and hospitals without PCI facilities

These centres receive STEMI patients through two different pathways - directly from home or the community, or via transfer by EMS. Non-pPCI centres should diagnose a STEMI within 10 minutes after the patient’s arrival and perform pPCI or transfer to a pPCI centre, or handle a PI strategy (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2).

Primary PCI centres

pPCI centres receive STEMI patients through one of three pathways - directly from home or the community, via transfer by EMS, or by secondary transportation from a non-pPCI centre. They should have a mandatory 24/7 cath lab available within 30 minutes of activation. They are obliged to operate a “non-refusal” admission policy (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Table 2).

Setting up a STEMI network

Despite national or regional challenges, the implementation of a STEMI network is always similar.

Stage 1. Preparation phase

The first step is to set up a local task force and an action plan for developing the network. This task force is also responsible for assigning roles, developing standard protocols for diagnosis and treatment in cooperation with the regional stakeholders and, later, coordinating the network.

Stage 2. Mapping phase

In this phase, the task force identifies all potential pPCI and non-pPCI centres, estimates the distances and the time needed for transportation, checks the availability of EMS and contacts the centres and the EMS to confirm their willingness to participate and their ability to cope with the demands. All these resources should be mapped to understand the regional situation and to determine the best possible layout of regional network(s).

Stage 3. Building phase

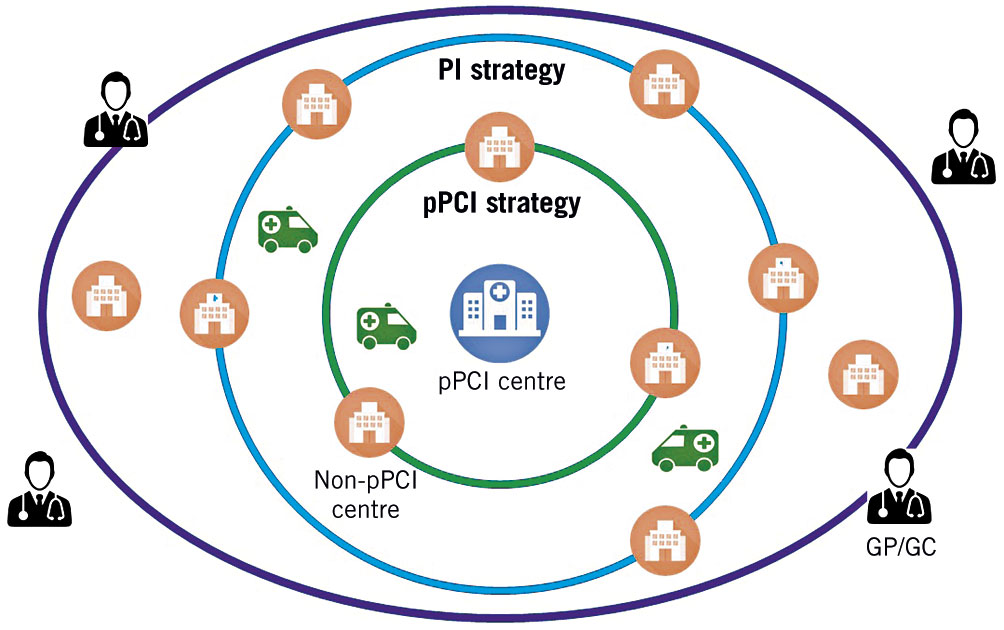

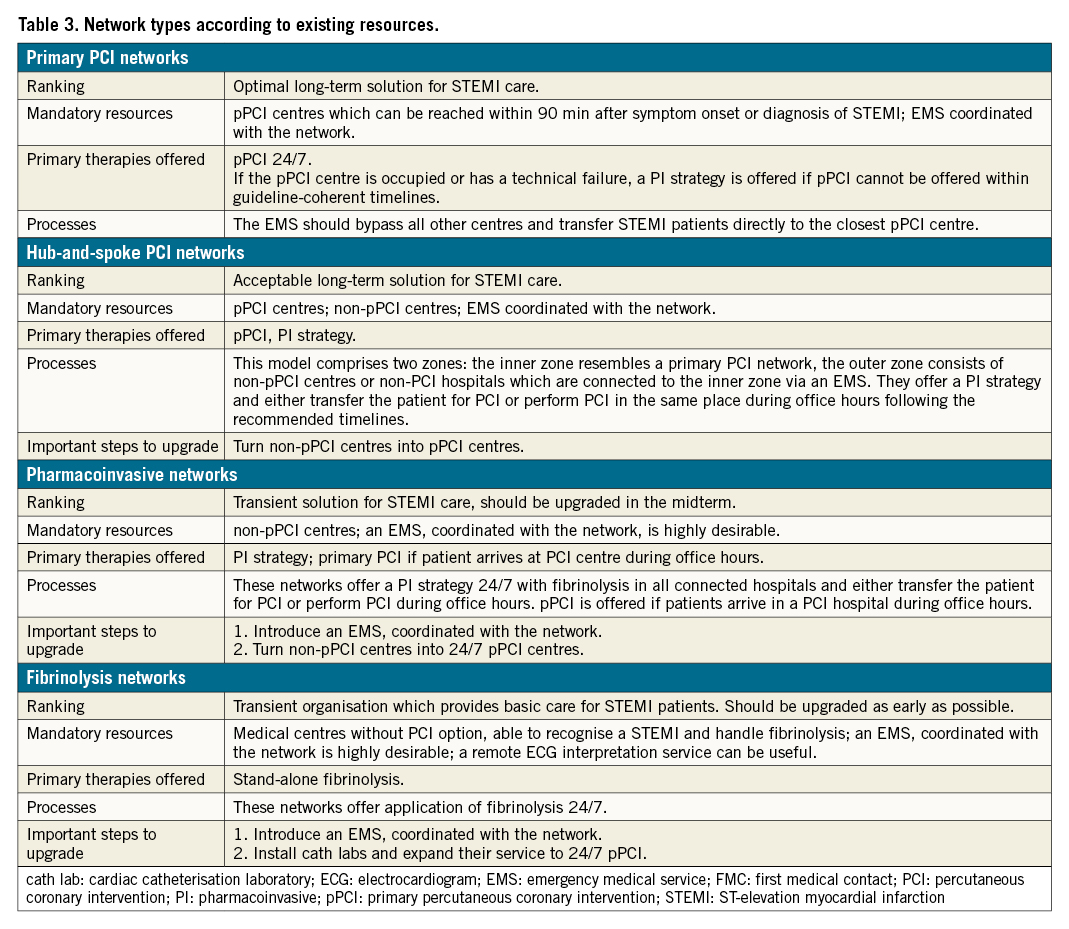

Following the assumption that the role of each player in any network is always defined by the presence or absence of other players, any network can be categorised following the specifications in Table 3 and the Central illustration. The task force assigns the individual roles to each player and nominates the coordinators of the centres, the EMS, and the GP/GC groups.

Central illustration. Typical combination of a hub-and-spoke network with an inner zone (green circle) organised as a pPCI network and an outer zone following a PI strategy (blue circle). The external purple zone represents a fibrinolysis network with no PCI centre in reach. GP/GC: general practitioner/general cardiologist; PI: pharmacoinvasive; pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Stage 4. Quality assessment and continuous education phase

Quality assessment

At least one basic set (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4) of quality variables should be established7. This refers to the performance parameters of all network components and includes, e.g., presentation timing, rate of patients treated, procedural success and in-hospital mortality. The task force should meet periodically to analyse the performance and discuss necessary adaptations. The connection of reimbursement and compliance with standards can be a relevant steering instrument11. One question that remains unanswered is whether having too many pPCI centres in a region may be disadvantageous, since each single centre could end up having not enough experience and routine practice.

Continuous education for professionals

Not all professionals involved have a basic training in cardiology. It may be important to offer specific educational and training programmes for paramedics, nurses, technicians and non-cardiology physicians on a recurrent basis due to staff rotation.

Population awareness campaigns

Patient awareness of indicative symptoms and knowledge of how to seek medical attention effectively is key for the success of a STEMI network programme, since the longest delays are usually caused by the patients12. Awareness programmes involving social media, the entertainment industry, community organisations and scientific associations may be helpful; however, their effects quickly fade once they are discontinued13.

Conclusions

The implementation of regional STEMI care systems overcomes local barriers and guarantees the best available reperfusion treatment for STEMI patients. A coordinated network of all stakeholders, guided by evidence-based, standardised protocols with a clear definition of roles and responsibilities is key and should be accompanied by a process of continuous improvement through evaluation of quality measures.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

The list of references can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.