Abstract

Background

Very long-term outcomes according to diabetic status of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with new-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) are scant. Both, the durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent (DP-ZES), the first DES to gain FDA-approval for specific use in patients with diabetes mellitus, and the polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stent (PF-SES), with a unique design that enables effective drug release without the need of a polymer offer the potential to enhance clinical long-term outcomes especially in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Methods

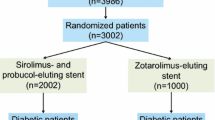

We investigate 10-year clinical outcomes of the prespecified subgroups of patients with and without diabetes mellitus, randomly assigned to treatment with PF-SES versus DP-ZES in the ISAR-TEST 5 trial. The primary endpoint of interest was major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as the composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction or any revascularization. Further endpoints of interest were cardiac death, myocardial infarction related to the target vessel and target lesion revascularization as well as the individual components of the primary composite endpoint and the incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis at 10 years.

Results

This analysis includes a total of 3002 patients randomly assigned to PF-SES (n = 2002) or DP-ZES (n = 1000). Prevalence of diabetes mellitus was high and comparable, 575 Patients (28.7%) in PF-SES group and 295 patients (29.5%) in DP-ZES group (P = 0.66). At 10 years 53.5% of patients with diabetes mellitus and 68.5% of patients without diabetes mellitus were alive. Regarding major adverse cardiac events, PF-SES as compared to DP-ZES showed comparable event rates in patients with diabetes mellitus (74.8% vs. 79.6%; hazard ratio 0.86; 95% CI 0.73–1.02; P = 0.08) and in patients without diabetes (PF-SES 62.5% vs. DP-ZES 62.2%; hazard ratio 0.99; 95% CI 0.88–1.11; P = 0.88).

Conclusion

At 10 years, both new-generation DES show comparable clinical outcome irrespective of diabetic status or polymer strategy. Event rates after PCI in patients with diabetes mellitus are considerable higher than in patients without diabetes mellitus and continue to accrue over time.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00598533, Registered 10 January 2008, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00598533?term=NCT00598533

Graphic abstract

Kaplan-Meier estimates of endpoints of interest for patients with vs. without diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES vs. DP-ZES. Bar graphs: Kaplan-Meier estimates as percentages. PF-SES: polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent; DP-ZES: durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent; DM: diabetes mellitus. Comparison of event rates of individual endpoints in patients with and without diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES vs. DP-ZES all without statistically significant differences. Comparison of event rates of individual endpoints in overall patients with vs. without diabetes mellitus significantly different (P ≤ 0.01 for all comparisons).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes mellitus is associated with numerous acute and late complications affecting different organ systems. However, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this population. In this vein, myocardial revascularization strategies remain a crucial part of the treatment of these patients [1, 2]. While current evidence favors coronary artery bypass grafting as the treatment of choice in patients with diabetes and complex multivessel disease, the growing number of patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation in complex disease including left main stenosis and patients with increased surgical risk remains considerable [2, 3].

Since atherosclerotic lesions in patients with diabetes mellitus are known to present greater inflammation than in other patients [4], device innovations specifically address the drug-carrying polymer attempting to reduce polymer-induced inflammatory stimuli, as had been revealed by pathology studies [5, 6]. Different approaches to meet this issue included permanent polymers with improved biocompatibility and polymer-free DES. In this vein, the first device to gain FDA approval for specific use in diabetic patients was the zotarolimus-eluting stent, based on a specific durable polymer with higher biocompatibility (DP-ZES) [7]. On the other hand, the polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stent (PF-SES) is a DES with a unique design that enables effective drug release without the need of a polymer. Although the effects of which are believed to become evident over time, very long-term outcomes of diabetic patients treated with either of these DES beyond 5-year follow-up have not been assessed to date.

In this context, we report 10-year clinical outcomes of the prespecified subgroups of patients with and without diabetes mellitus, enrolled in the ISAR-TEST 5 randomized controlled trial to compare a polymer-free probucol- and sirolimus-eluting stent versus a new-generation durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent in coronary artery disease.

Methods

Study population, device description and study protocol

The primary analysis, including full details of the study population, methods and endpoints, of the ISAR-Test 5 trial was previously reported [8]. Patients with diabetes mellitus represented a prespecified subgroup of interest according to the trial protocol. In brief, ISAR-Test 5 was a randomized controlled trial, that enrolled patients older than 18 years of age with ischaemic symptoms or evidence of myocardial ischaemia (inducible or spontaneous) in the presence of written, informed consent by the patient or her/his legally authorized representative for participation in the study was obtained. Patients with a target lesion located in the left main stem, cardiogenic shock, malignancies or other co-morbid conditions with life expectancy less than 12 months or that may result in protocol non-compliance, known allergy to the study medications (probucol, sirolimus, zotarolimus) or pregnancy (present, suspected or planned) were considered ineligible for the study. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the two participating centers: Deutsches Herzzentrum München and 1. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, both in Munich, Germany.

Patients who met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were randomized in the order that they qualified. Patients were assigned to receive polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stents or durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stents in a 2:1 allocation. The polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stents consists of a pre-mounted, sand-blasted, thin-strut 316L stainless steel microporous stent which is coated with a mixture of sirolimus, probucol, and shellac resin (a biocompatible resin widely used in the coating of medical tablets). (This coating strategy is currently available in two devices: ISAR VIVO, Translumina Therapeutics, Dehradoon, India, Translumina, Hechingen, Germany and Coroflex ISAR, B. Braun Melsungen, Berlin, Germany.) The durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent (Resolute, Medtronic Cardiovascular, Santa Rosa, CA) consists of a thin-strut 91-µm stent platform. The polymer-coating system consists of three different polymers: a hydrophobic C10 polymer, a hydrophilic C19 polymer and polyvinylpyrrolidinone. Further detailed descriptions of stent platforms and elution characteristics of both stents have been reported previously [9,10,11,12]. The aim of the current study was to compare outcomes of patients treated with polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stents versus durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent after extended clinical follow-up out to 10 years.

End points, and definitions

The primary endpoint of the present analysis was the composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction or any revascularization (major adverse cardiac events; MACE). Further endpoints of interest were cardiac death, myocardial infarction related to the target vessel and target lesion revascularization at 10 years, as well as the individual components of the primary composite endpoint and the incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis (by Academic Research Consortium definition) at 10 years. Detailed description of study endpoints and definitions have also been reported previously [8].

Follow-up and analysis

Patients were systematically evaluated at 1 and 12 months and annually out to 10 years. Extended follow-up was performed in the setting of routine care by either telephone calls or office visit in the two participating centers. The study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the clinical trial. Analysis of data from extended follow-up, which was not prespecified in the trial protocol, was approved by the institutional ethics committee responsible for the participating centers. Additional written informed consent from patients was waived. All events were adjudicated and classified by an event adjudication committee blinded to treatment allocation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or median [25th–75th percentiles]. Categorical data are presented as counts or proportions (%). Data distribution was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for goodness of fit. For patient-level data, differences between groups were checked for significance using Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test (continuous data) or the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test where the expected cell value was < 5 (categorical variables). For lesion level data, differences between groups were checked for significance using generalized estimating equations for non-normally distributed data to address intra-patient correlation in patients who underwent multi-lesion intervention [13].

Event-free survival was assessed using the methods of Kaplan–Meier. Hazard ratios, confidence intervals and p values were calculated from univariate Cox proportional hazards models. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by the method of Grambsch and Therneau [14] and was fulfilled in all cases in which we used Cox proportional hazards models. The analysis of all endpoints was planned to be performed on an intention-to-treat basis [15]. Statistical software R, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for analysis.

Results

This analysis includes a total of 3002 patients with coronary artery disease randomized to treatment with either polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stents (PF-SES: n = 2002) or durable zotarolimus-eluting stents (DP-ZES: n = 1000) in the setting of the randomized ISAR-TEST 5 trial.

Prevalence of diabetes mellitus was high, 870 patients (29.0%), and comparable in both treatment groups. 575 Patients (28.7%) who received PF-SES and 295 patients (29.5%) who received DP-ZES had diabetes (P = 0.66). Over the course of 10-year clinical follow-up, 67 patients treated with PF-SES (4.7%) and 22 patients treated with DP-ZES (3.12%) were newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (P = 0.111). Overall baseline characteristics according to diabetic status are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to diabetic status and treatment group are summarized in Table 1. Baseline patient and lesion characteristics were well balanced between both treatment groups, except one: patients without diabetes mellitus and treated with DP-ZES had significantly more often hyperlipidemia than those who received PF-SES (65.5% vs. 60.8%, P = 0.04). 10-year clinical follow-up was completed in 85.1% of the study population, follow-up details have been previously described in detail [16].

Clinical outcomes of PF-SES versus DP-ZES in patients with and without diabetes mellitus at 10 years

Clinical results according to diabetic status (patients without and with diabetes mellitus) are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Clinical results according to diabetic status and treatment group are summarized in Table 2.

Concerning the composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction and any revascularization, rates were high but comparable in patients with diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES as compared to DP-ZES (74.8% vs. 79.6%; P = 0.08; hazard ratio 0.86; 95% CI 0.73–1.02) and patients without diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 62.5% vs. DP-ZES 62.2%; P = 0.88; hazard ratio 0.99; 95% CI 0.88–1.11). Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidence of major adverse cardiac events according to treatment group and diabetic status are displayed in Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for incidence of major adverse cardiac events according to treatment group and diabetic status. PF-SES polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent, DP-ZES durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent, DM diabetes mellitus, MACE major adverse cardiac events, HR hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models, CI confidence interval, Poverall with vs. without DM indicates the overall comparison of patients with diabetes versus patients without diabetes irrespective of stent type

At 10 years, 53.5% of patients with diabetes mellitus and 68.5% of patients without diabetes mellitus were alive. All-cause mortality rates were comparable in patients with diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES as compared to DP-ZES (44.8% vs. 50.1%; P = 0.11; hazard ratio 0.84; 95% CI 0.68–1.04) and patients without diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 31.2% vs. DP-ZES 32.0%; P = 0.60; hazard ratio 0.96; 95% CI 0.81–1.13). Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidence of all-cause death according to treatment group and diabetic status are displayed in Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for incidence of all-cause death according to treatment group and diabetic status. PF-SES polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent, DP-ZES durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent, DM diabetes mellitus, HR hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models, CI confidence interval, Poverall with vs. without DM indicates the overall comparison of patients with diabetes versus patients without diabetes irrespective of stent type

Rates of cardiac death at 10 years were comparable between PF-SES and DP-ZES in patients with diabetes (36.0% vs. 39.3%; P = 0.38; hazard ratio 0.89; 95% CI 0.69–1.15). Patients without diabetes had overall lower rates of cardiac death, but without any significant difference between treatment groups (PF-SES 23.2% vs. DP-ZES 22.0%; P = 0.60; hazard ratio 1.06; 95% CI 0.86–1.31). Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidence of cardiac mortality according to treatment group and diabetic status are displayed in Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for incidence of cardiac mortality according to treatment group and diabetic status. PF-SES polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent, DP-ZES durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent, DM diabetes mellitus, HR hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models, CI confidence interval, Poverall with vs. without DM indicates the overall comparison of patients with diabetes versus patients without diabetes irrespective of stent type

Regarding the incidence of any myocardial infarction at 10 years, there was no significant difference between PF-SES and DP-ZES in patients with diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 8.0% vs. DP-ZES 8.3%; P = 0.92, hazard ratio 0.97; 95% CI 0.58–1.63) and patients without diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 4.7% vs. DP-ZES 4.7%, P = 0.99, hazard ratio 1.00; 95% CI 0.64–1.54).

Regarding the incidence of target vessel related myocardial infarction at 10 years there was no significant difference between PF-SES and DP-ZES in patients with diabetes (PF-SES 4.9% vs. DP-ZES 7.3%, P = 0.27; hazard ratio 0.72; 95% CI 0.40–1.30) and without diabetes (PF-SES 3.3% vs. DP-ZES 3.3%, P = 0.80; hazard ratio 0.94; 95% CI 0.56–1.57).

Rates for any revascularization were high but comparable in patients with diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES as compared to DP-ZES (PF-SES 53.2% vs. DP-ZES 57.4%; P = 0.43, hazard ratio 0.92; 95% CI 0.75–1.13) and patients without diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 42.6% vs. 42.3%; P = 0.97, hazard ratio 1.00; 95% CI 0.90–1.16). Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidence of any revascularization according to treatment group and diabetic status are displayed in Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for incidence of any revascularization according to treatment group and diabetic status. PF-SES polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent, DP-ZES durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent, DM diabetes mellitus, HR hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models, CI confidence interval, Poverall with vs. without DM indicates the overall comparison of patients with diabetes versus patients without diabetes irrespective of stent type

Regarding the incidence of target lesion revascularization in patients with diabetes, rates were comparable in both treatment groups (PF-SES 27.1% vs. DP-ZES 29.7%; P = 0.75; hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% CI 0.71–1.28). In patients without diabetes, rates were comparable in both treatment groups (PF-SES 20.0% vs. DP-ZES 17.5%; P = 0.43; hazard ratio 1.10; 95% CI 0.87–1.37). Kaplan–Meier curves for the incidence of target lesion revascularization according to treatment group and diabetic status are displayed in Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for incidence of target lesion revascularization according to treatment group and diabetic status. PF-SES polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent, DP-ZES durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent, DM diabetes mellitus, HR hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models, CI confidence interval, Poverall with vs. without DM indicates the overall comparison of patients with diabetes versus patients without diabetes irrespective of stent type

Safety outcomes

Regarding safety outcomes, rates of definite/probable stent thrombosis were low and comparable in patients with diabetes mellitus treated with PF-SES as compared to DP-ZES (PF-SES 2.5% vs. DP-ZES 2.5%; P = 0.97, hazard ratio 1.02; 95% CI 0.41–2.52) and patients without diabetes mellitus (PF-SES 1.2% vs. DP-ZES 1.6%; P = 0.45, hazard ratio 0.74; 95% CI 0.33–1.64). Detailed results concerning incidence of definite, probable stent thrombosis according to diabetic status and treatment group are displayed in Table 3. Results concerning incidence of definite, probable stent thrombosis according to diabetic status are displayed in Supplemental Table 3.

Discussion

The present analysis represents a valuable addition to a limited data-set of extended long-term clinical outcome comparisons of new-generation DES and the first report of 10-year clinical outcomes of both: the durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stents as well as the polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stent in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. The main findings of the present study are: first, at 10 years, there was no significant difference in the incidence of both device- and patient-oriented endpoints between patients treated with DP-ZES versus PF-SES, neither in the subgroup of patients with diabetes mellitus nor in the subgroup of patients without diabetes mellitus. Second, irrespective of stent type, overall clinical event rates were considerably worse in patients with diabetes mellitus as compared to patients without diabetes mellitus.

Long-term follow-up in current DES trials

In recent years, increasing consideration has been given to the long-term outcomes (> 5 years) post-PCI [16, 17]. This represents an important shift in focus to the safety and efficacy of these devices over the lifespan of the patient. This might be of particular importance in patient subgroups with persistent higher event rates over time, such as patients with diabetes mellitus. However, traditionally, stent trials have focused on shorter term outcomes, and therefore, current data including this specific high-risk subgroup of patients are limited [18, 19]. Two considerations should be taken into account. First, it has been suggested that the benefit of enhanced polymer strategies, may emerge over time [17]. Second, iterations in stent design aiming on a reduction of persistent inflammatory stimulus caused by permanent polymers might be most beneficial in patients with diabetes mellitus, given the proinflammatory baseline environment in these patients [4].

New-generation DES and thrombotic events

After preclinical research had revealed that durable polymer might be associated with impaired vascular healing after stent implantation and, therefore, potentially increase the risk for late thrombotic events [5, 6], trials began to evaluate alternative polymer-based and non-polymer-based drug-elution strategies. Different new-generation stent types emerged from these efforts, including polymer-free DES [20]. One promising group of patients in which polymer-free DES are currently being investigated are patients with diabetes mellitus [18, 21, 22]. The low incidence of thrombotic events at 10 years, in this study, with either new-generation DES, PF-SES or DP-ZES is reassuring, and underlines that new-generation DES might have overcome one major drawback of early-generation permanent-polymer DES. This is particularly true concerning late stent thrombosis, with only one event in the overall cohort beyond 12 months. On the other hand, the two-fold higher rates of stent thrombosis in patients with diabetes mellitus at 10 years as compared to patients without diabetes mellitus is noteworthy. Along with these results, the rates of myocardial infarction in this analysis deserve further attention. Interestingly, while target vessel MI rates at 10 years remain two-fold higher in patients with—as compared to patients without—diabetes mellitus, overall event-rates beyond 5 years remain negligible. In contrast, any myocardial infarction continues to occur constantly out to 10 years to 8.1% of patients with diabetes mellitus as compared to 4.7% in non-diabetic patients (P < 0.001). This underlines the importance of specific considerations concerning concomitant antithrombotic treatment regimes in patients with diabetes mellitus [23].

Clinical outcomes at 10 years

Concerning clinical outcomes, in this study, PF-SES has demonstrated comparable but not superior long-term outcomes as compared to new-generation durable polymer ZES. Although, these results are broadly in line with previous results at 5 years in a dedicated analysis of patients with diabetes mellitus and the 10-year results of the overall cohort [16, 18], the cumulative 10-year event rate of almost 80% in patients with diabetes mellitus remains alarming. Therefore, some findings concerning the individual endpoints of interest beyond 5 years deserve further consideration. First, in this analysis, irrespective of diabetic status, rather patient-oriented endpoints—such as any revascularization and all-cause mortality—predominate over rather device-specific endpoints. Accordingly, rates of any revascularization are two-fold higher than target lesion revascularization rates at 10 years in both, patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Additionally, diabetes mellitus is associated with a significant increased 38% relative risk of any revascularization. Both findings are in line with previous observations [24], and underline that disease progression in other coronary segments has greater impact on late clinical outcomes than recurrent events in the intervened lesion. Our data suggest, that this seems specifically true for patients with diabetes mellitus potentially due to a more defuse type of CAD. Concerning mortality, unsurprisingly both cardiac and all-cause mortality was higher in patients with diabetes mellitus as compared to patients without diabetes. Noteworthy, the majority of diabetic patients (70%) died from cardiac cause. Although, these findings contradict to previous registry-based long-term data reporting, that mortality, beyond 1 year after PCI, is mainly driven by non-cardiac death [25], these results underline that cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients with CAD.

Polymer-free DES in diabetic patients

Besides the PF-SES investigated in the present study, data from randomized trials and large multicenter registries are available for two further new-generation devices: the polymer-free amphilimus-eluting (PF-AES) and biolimus-eluting (PF-BES) stents, although with follow-up duration not longer than 5 years. In patients with diabetes mellitus, the PF-BES showed superior efficacy and comparable safety over bare-metal stent in the respective subgroup analysis of the LEADERS FREE trial [21]. However, PF-BES failed to meet criteria for non-inferiority when compared to a new-generation ultrathin-strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent in the all-comer SORT-OUT IX randomized trial [26]. The longest term data for PF-AES also derive from the respective first in man trial. The NEXT trial randomized selected patients to treatment with either PF-AES or early-generation DES. In this trial, in patients with diabetes mellitus treatment with PF-AES seemed to lower the incidence of the device-oriented composite endpoint to a similar level as patients without diabetes mellitus [22]. Data from randomized comparisons of PF-AES to new-generation DES are only available from two trials. The ReCr8 trial, an all-comer non-inferiority trial, assessed clinical outcome of patients treated with PF-AES or new-generation DP-ZES. Regarding the device-oriented endpoint non-inferiority was met as no meaningful differences were observed at 12 moths. Furthermore, there were no significant differences regarding the predefined subgroup of patients with diabetes mellitus [27]. In the smaller RESERVOIR trial, 112 patients with diabetes mellitus were randomized to treatment with PF-AES or benchmark new-generation DES with permanent polymer and angiographic as well as optical coherence tomography outcomes were assessed. With respect to the primary endpoint—neointimal volume obstruction—non-inferiority of PF-AES as compared to benchmark DES in patients with diabetes mellitus was met. As expected, clinical outcomes did not differ between both study groups [28].

Comparison of the results of these trials with the results of the present analysis is not feasible due to important differences regarding patient selection criteria and follow-up duration. Of note, study devices in dedicated randomized trials do not only differ in polymer characteristics but also other features like backbone architecture or antiproliferative drugs. For that reason, neither superiority of one device over another could undeniably be attributed to their respective polymer nor do comparable outcomes necessarily lead to rejection of the hypothesis that polymer in fact makes a difference. With respect to the present trial, the absence of significant clinical outcome differences warrants the conclusions that the effect of the coating concept alone is either non-existent or below the detection limit determined by the trial design, while both study devices represent reasonable treatment options for both patients with and patients without diabetes mellitus. Future, specifically dedicated trials are warranted to further investigate the hypothesis that tailored stent design has the potential to be part of the integrative approach to cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. In this context, results of the ongoing SUGAR trial are therefore eagerly awaited [29].

The observation of a higher incidence of clinical events out to 10 years after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes mellitus as compared to patients without diabetes mellitus as well as the constant accrual of events over time underlines the high cardiovascular risk patients suffering from this frequent metabolic disorder are exposed to. Continued efforts to improve prevention and treatment of diabetes mellitus are, therefore, of ongoing importance.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Although this analysis is the first to report clinical follow-up out to 10 years after treatment with PF-SES or DP-ZES, the trial was not specifically powered for a comparison of clinical outcomes in the subgroup of patients with or without diabetes mellitus. The present analysis is a post hoc analysis and, therefore, vulnerable to all methodical flaws inherent to post hoc analysis of such kind of subgroups and the respective findings need to be interpreted against this background. Furthermore, while long-term follow-up is an important strength of the present analysis, with longer follow-up duration diabetes status will change in some cases and potentially dilute findings regarding the comparison of patients with vs. without diabetes mellitus. Interestingly however, during 10-year follow-up less than 5% of patients were newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

Conclusion

At 10 years, both new-generation DES show comparable clinical outcome irrespective of diabetic status or polymer strategy. Event rates after PCI in patients with diabetes mellitus are considerable higher than in patients without diabetes mellitus and continue to accrue over time.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets on which the conclusions of the manuscript are based are presently not deposited in a publicly accessible repository as the ethics committee approval from the Technische Universität München (2007) did not foresee provision for this.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- DES:

-

Drug-eluting stent

- PF-SES:

-

Polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stent

- DP-ZES:

-

Durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

- PF-AES:

-

Polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent

- PF-BES:

-

Polymer-free biolimus-eluting stent

References

Arnold SV, Bhatt DL, Barsness GW, Beatty AL, Deedwania PC, Inzucchi SE et al (2020) Clinical management of stable coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 141:1–28

Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V et al (2019) ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 2019:3035–3087

Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U et al (2018) 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 46(4):517–592

Yahagi K, Kolodgie FD, Lutter C, Mori H, Romero ME, Finn AV et al (2017) Pathology of human coronary and carotid artery atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 37(2):191–204

Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E et al (2006) Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans. Delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 48(1):193–202

Finn AV, Nakazawa G, Joner M, Kolodgie FD, Mont EK, Gold HK et al (2007) Vascular responses to drug eluting stents: importance of delayed healing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(7):1500–1510

Silber S, Serruys PW, Leon MB, Meredith IT, Windecker S, Neumann FJ et al (2013) Clinical outcome of patients with and without diabetes mellitus after percutaneous coronary intervention with the resolute zotarolimus-eluting stent: 2-year results from the prospectively pooled analysis of the International Global RESOLUTE Program. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 6(4):357–368

Massberg S, Byrne RA, Kastrati A, Schulz S, Pache J, Hausleiter J et al (2011) Polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting versus new generation zotarolimus-eluting stents in coronary artery disease: the intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: test efficacy of sirolimus- and probucol-eluting versus zotarolimus-eluting sten. Circulation 124(5):624–632

Byrne RA, Mehilli J, Iijima R, Schulz S, Pache J, Seyfarth M et al (2009) A polymer-free dual drug-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized trial vs polymer-based drug-eluting stents. Eur Heart J. 30(8):923–931

Meredith IT, Worthley S, Whitbourn R, Walters D, Popma J, Cutlip D et al (2007) The next-generation Endeavor Resolute stent: 4-month clinical and angiographic results from the Endeavor Resolute first-in-man trial. EuroIntervention 3(1):50–53

Steigerwald K, Merl S, Kastrati A, Wieczorek A, Vorpahl M, Mannhold R et al (2009) The pre-clinical assessment of rapamycin-eluting, durable polymer-free stent coating concepts. Biomaterials 30(4):632–637

Wessely R, Hausleiter J, Michaelis C, Jaschke B, Vogeser M, Milz S et al (2005) Inhibition of neointima formation by a novel drug-eluting stent system that allows for dose-adjustable, multiple, and on-site stent coating. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25(4):748–753

Zeger SL, Liang K-Y (1986) Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics

Grambsch PM, Therneau TM (1994) Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81(3):515–526

Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW, CONSORT Group (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA 295(10):1152

Kufner S, Ernst M, Cassese S, Joner M, Mayer K, Colleran R et al (2020) 10-year outcomes from a randomized trial of polymer-free versus durable polymer drug-eluting coronary stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 76(2):146–158

Kufner S, Joner M, Thannheimer A, Hoppmann P, Ibrahim T, Mayer K et al (2019) Ten-year clinical outcomes from a trial of three limus-eluting stents with different polymer coatings in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 139(3):325–333

Harada Y, Colleran R, Kufner S, Giacoppo D, Rheude T, Michel J et al (2016) Five-year clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus treated with polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting stents versus second-generation zotarolimus-eluting stents: a subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol 15(1):1–10

Iqbal J, Serruys PW, Silber S, Kelbaek H, Richardt G, Morel MA et al (2015) Comparison of zotarolimus-and everolimus-eluting coronary stents: final 5-year report of the RESOLUTE all-comers trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 8(6):1–8

Byrne RA, Stone GW, Ormiston J, Kastrati A (2017) Coronary balloon angioplasty, stents, and scaffolds. Lancet 390(10096):781–792

Richardt G, Maillard L, Nazzaro MS, Abdel-Wahab M, Carrié D, Iñiguez A et al (2019) Polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents in diabetic patients at high bleeding risk: a pre-specified sub-study of the LEADERS FREE trial. Clin Res Cardiol 108(1):31–38

Carrié D, Berland J, Verheye S, Hauptmann KE, Vrolix M, Musto C et al (2020) Five-year clinical outcome of multicenter randomized trial comparing amphilimus - with paclitaxel-eluting stents in de novo native coronary artery lesions. Int J Cardiol. 301:50–55

Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Mehta SR, Leiter LA, Simon T, Fox K et al (2019) Ticagrelor in patients with diabetes and stable coronary artery disease with a history of previous percutaneous coronary intervention (THEMIS-PCI): a phase 3, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet

Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, De Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS et al (2011) A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 364(3):226–235

Spoon DB, Psaltis PJ, Singh M, Holmes DR, Gersh BJ, Rihal CS et al (2014) Trends in cause of death after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 129(12):1286–1294

Jensen LO, Ellert J, Veien KT, Ahlehoff O, Hansen KN, Aziz A et al (2020) Randomized comparison of the polymer-free biolimus-coated biofreedom stent with the ultrathin strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting orsiro stent in an all-comers population treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: the SORT out IX Trial. Circulation 2052–2063

Rozemeijer R, Stein M, Voskuil M, Van Den Bor R, Frambach P, Pereira B et al (2019) Randomized all-comers evaluation of a permanent polymer zotarolimus-eluting stent versus a polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent: multicenter, noninferiority trial (ReCre8). Circulation 139(1):67–77

Romaguera R, Gómez-Hospital JA, Gomez-Lara J, Brugaletta S, Pinar E, Jiménez-Quevedo P et al (2016) A randomized comparison of reservoir-based polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stents versus everolimus-eluting stents with durable polymer in patients with diabetes mellitus the RESERVOIR clinical trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 9(1):42–50

Romaguera R, Salinas P, Brugaletta S, Gomez-Lara J, Díaz JF, Romero MA et al (2020) Second-generation drug-eluting stents in diabetes (SUGAR) trial: rationale and study design. Am Heart J 222:174–182

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study sponsor was Deutsches Herzzentrum Muenchen. Funding was provided in part by the Bavarian Research Foundation (BFS-ISAR Aktenzeichen AZ: 504/02 and BFS-DES Aktenzeichen AZ: 668/05) and by the European Union under the Seventh Frame Work Programme (FP7 PRESTIGE 260309).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

TK, TL, AK and SK made substantial contributions to conception and design of the present analysis. All authors were involved in acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. TL, TK and SK drafted the first version of the manuscript; MJ, EX, TK, JW, J-JC, AA, TI, TK, SC, K-LL and HS revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MJ reports speaker fees from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, AstraZeneca, Coramaze, and OrbusNeich, as well as research grants from Biotronik and the European Society of Cardiology; JW reports minor speaker fees from Astra Zeneca; HS reports honoraria fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, MSD SHARP&DOHME, Novartis, Servier, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, Pfizer and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Amgen, MSD SHARP&DOHME; SK reports speaker fees from Astra Zeneca, speaker and consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and speaker and consulting fees from Translumina, all other authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the two participating centers: Deutsches Herzzentrum München and 1. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum rechts der Isar, both in Munich, Germany.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koch, T., Lenz, T., Joner, M. et al. Ten-year clinical outcomes of polymer-free versus durable polymer new-generation drug-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease with and without diabetes mellitus. Clin Res Cardiol 110, 1586–1598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01854-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01854-7