-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matteo Bianco, Alessandro Careggio, Paola Destefanis, Alessia Luciano, Maria Giulia Perrelli, Giorgio Quadri, Roberta Rossini, Gianluca Campo, Giampiero Vizzari, Fabrizio D’Ascenzo, Matteo Anselmino, Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai, Borja Ibáñez, Laura Montagna, Ferdinando Varbella, Enrico Cerrato, P2Y12 inhibitors monotherapy after short course of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials including 29 089 patients, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 7, Issue 3, May 2021, Pages 196–205, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) reduces the incidence of thrombotic complications at the cost of an increase in bleedings. New antiplatelet therapies focused on minimizing bleeding and maximizing antithrombotic effects are emerging. The aim of this study is to collect the current evidence coming from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on early aspirin interruption after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and current drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation and to perform a meta-analysis in order to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this strategy.

MEDLINE/PubMed was systematically screened for RCTs comparing P2Y12 inhibitors (P2Y12i) monotherapy after a maximum of 3 months of DAPT (S-DAPT) vs. DAPT for 12 months (DAPT) in patients undergoing PCI with DES. Baseline features were appraised. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE: all causes of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) and its single composites, stent thrombosis (ST) and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3 or 5 were considered and pooled with fixed and random-effects with inverse‐variance weighting. A total of four RCTs including a total of 29 089 patients were identified. Overall, the majority of included patients suffered a stable coronary artery disease, while ST-elevation myocardial infarction was the least represented clinical presentation. Complex anatomical settings like left main intervention, bifurcations, and multi-lesions treatment were included although representing a minor part of the cases. At 1-year follow-up, MACCE rate was similar [odds ratio (OR) 0.90; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) 0.79–1.03] and any of its composites (all causes of death rate: OR 0.87; 95% CIs 0.71–1.06; myocardial infarction: OR 1.06; 95% CIs 0.90–1.26; stroke: OR 1.12; 95% CIs 0.82–1.53). Similarly, also ST rate was comparable in the two groups (OR 1.17; 95% CIs 0.83–1.64), while BARC 3 or 5 bleeding resulted significantly lower, adopting an S-DAPT strategy (OR 0.70; 95% CIs 0.58–0.86).

After a PCI with current DES, an S-DAPT strategy followed by a P2Y12i monotherapy was associated with a lower incidence of clinically relevant bleeding compared to 12 months DAPT, with no significant differences in terms of 1-year cardiovascular events.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor (P2Y12i) is the cornerstone of therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) treated with a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1–3 Dual antiplatelet therapy reduces the incidence of thrombotic complications but at the same time increases the incidence of bleeding complications that are directly connected with an increase in mortality.4,5

The recent development of stents with a less pro-thrombotic profile and the need to reduce bleedings without a thrombotic trade-off have opened the field to studies investigating new antiplatelet strategies after PCI.6

Some pre-clinical studies have shown the key role of P2Y12i over aspirin in platelet activation pushing investigators to explore the hypothesis of withdrawing aspirin after a short period following PCI in order to better balance the risk of bleeding and the prevention of ischaemic events.7,8 Based on these observations, some studies focused on early interruption of aspirin after 1 month or 3 months of DAPT maintaining a single antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12i.9

Aim of this study is to collect the current evidence coming from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on early aspirin interruption after PCI with current drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation and to perform a meta-analysis in order to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of this strategy.

Methods

Data sources

The terms ‘P2Y12 inhibitor’, ‘ticagrelor’, ‘prasugrel’, ‘clopidogrel’, ‘aspirin’ along with ‘monotherapy’ and ‘percutaneous coronary intervention’ were searched across MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases according to optimal search strategies.10

No language restrictions were imposed. The design and protocol of our systematic review and meta-analysis were previously published on PROSPERO registry (CRD42019149952).

Study selection

RCTs comparing P2Y12i monotherapy after a maximum of 3 months of DAPT vs. DAPT for at least 12 months in patients undergoing PCI for stable-CAD or ACS respectively with at least a 1-year follow-up were included. The outcomes of interest were (i) efficacy outcomes including (a) major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and its composites (all causes of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke); (b) definite/probable stent thrombosis (ST) (ii) safety outcome including Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3 or 5. Three investigators (E.C., M.B., and A.C.) independently appraised titles, abstracts, and the full texts to determine whether studies met inclusion criteria. Conflicts between reviewers were resolved through re-review and discussion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Three authors (E.C., M.B., and A.C.) independently abstracted data on study design, setting, antiplatelet drugs administered in experimental and control groups. Age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors and clinical presentations were also evaluated. Supplementary material online, Files were reviewed to extract any additional data of interest.

The quality of included trials was assessed according to Cochrane, PRISMA and QUORUM statements11,12; methods to obtain sample size, selection bias (allocation and random sequence generation), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), and attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) were assessed and graphically described. The Jadad Scale13 was used to appraise methodological quality of included studies. The population included in our meta-analysis was the sum of the populations included in the ‘intention to treat analysis’ of each single study selected.

Data synthesis and analysis

Fixed-effects models with generic inverse-variance weighting were used to compute dichotomous comparisons reporting odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each single outcome. Random-effects models were also tested and their results reported if different from random effect. Hypothesis testing for statistical homogeneity was set at the two-tailed 0.10 level and based on the Cochran Q test, with I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% representing mild, moderate, and extensive statistical heterogeneity, respectively. A funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test were performed to identify small study bias. RevMan 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Biostat Software, New York, USA) were used to perform the pooled analysis. Data analysed and reported in following study was available upon request contacting corresponding author.

Results

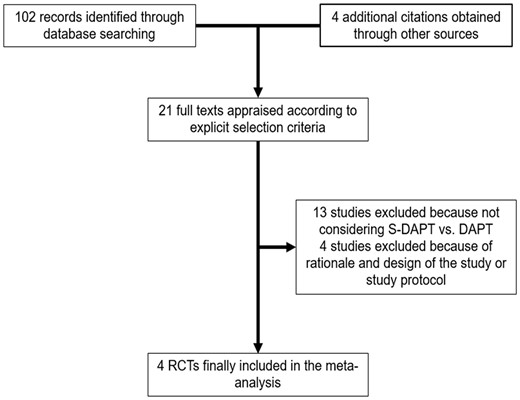

The abstracts of 102 studies were initially included and 21 were finally appraised as full text. Thirteen further studies were excluded because S-DAPT vs. DAPT were not considered; three studies were excluded because of different protocol design; one study because only the design and rationale of the trial were reported. Four RCTs were finally included14–17 encompassing 29 089 patients (Table 1). In STOPDAPT-2 and GLOBAL LEADERS, S-DAPT regimen was up to 1 month, while TWILIGHT and SMART-CHOICE studies prolonged the S-DAPT therapy up to 3 months. Both STOPDAPT-2 and SMART-CHOICE studies enrolled around 1500 patients from Japan and Korea, respectively, while GLOBAL LEADERS and TWILIGHT encompassed almost 8000 and 7000 patients, respectively from Europe, Canada, South America, North America, and Asia. Composite primary endpoint differs in each study but all endpoints of interests were reported and comparable through the different trials. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were substantially the same among all studies apart from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients that were excluded only in TWILIGHT trial.

Main features of included studies

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3555 vs. 3564 | 1500 vs. 1509 | 1495 vs. 1498 | 7980 vs. 7988 |

| Location | Austria, Canada, China, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Poland, Spain, UK, USA | Japan | Korea | Canada, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, UK, Denmark, Poland, Germany, Brazil, Australia, Singapore, Bulgaria |

| Study design | Randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Randomized, multicentre, open label, adjudicator-blinded clinical trial | Randomized, investigator-initiated, multicentre, open label, non-inferiority | Randomized, open label, superiority trial, multicentre, multinational |

| Funding | Sponsored by Icahn School of Medicine, investigator-initiated grant from AstraZeneca | Abbott Vascular funded the study but did not provide medications or coronary devices | Unrestricted grants from the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (grant 2013-3), Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific |

|

| Follow-up (months) | 15 (monthly from 3rd month) | 12 | 12 | 24 (landmark analysis at 1 and 12 months) |

| S-DAPT | 3 months DAPT regimen with aspirin 81–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimens, either aspirin 81–200 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or prasugrel 3.75 mg daily, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy | 3 months DAPT regimens, either aspirin 100 mg daily and clopidogrel 175 mg daily or prasugrel 10 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimen with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by 23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy |

| DAPT | 15 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimens with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months |

| Inclusion criteria | Must meet one of the following:

| Patients who underwent successful PCI with CoCr-EES (DES) |

|

|

Must meet one of the following:

| ||||

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3555 vs. 3564 | 1500 vs. 1509 | 1495 vs. 1498 | 7980 vs. 7988 |

| Location | Austria, Canada, China, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Poland, Spain, UK, USA | Japan | Korea | Canada, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, UK, Denmark, Poland, Germany, Brazil, Australia, Singapore, Bulgaria |

| Study design | Randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Randomized, multicentre, open label, adjudicator-blinded clinical trial | Randomized, investigator-initiated, multicentre, open label, non-inferiority | Randomized, open label, superiority trial, multicentre, multinational |

| Funding | Sponsored by Icahn School of Medicine, investigator-initiated grant from AstraZeneca | Abbott Vascular funded the study but did not provide medications or coronary devices | Unrestricted grants from the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (grant 2013-3), Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific |

|

| Follow-up (months) | 15 (monthly from 3rd month) | 12 | 12 | 24 (landmark analysis at 1 and 12 months) |

| S-DAPT | 3 months DAPT regimen with aspirin 81–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimens, either aspirin 81–200 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or prasugrel 3.75 mg daily, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy | 3 months DAPT regimens, either aspirin 100 mg daily and clopidogrel 175 mg daily or prasugrel 10 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimen with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by 23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy |

| DAPT | 15 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimens with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months |

| Inclusion criteria | Must meet one of the following:

| Patients who underwent successful PCI with CoCr-EES (DES) |

|

|

Must meet one of the following:

| ||||

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

Main features of included studies

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3555 vs. 3564 | 1500 vs. 1509 | 1495 vs. 1498 | 7980 vs. 7988 |

| Location | Austria, Canada, China, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Poland, Spain, UK, USA | Japan | Korea | Canada, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, UK, Denmark, Poland, Germany, Brazil, Australia, Singapore, Bulgaria |

| Study design | Randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Randomized, multicentre, open label, adjudicator-blinded clinical trial | Randomized, investigator-initiated, multicentre, open label, non-inferiority | Randomized, open label, superiority trial, multicentre, multinational |

| Funding | Sponsored by Icahn School of Medicine, investigator-initiated grant from AstraZeneca | Abbott Vascular funded the study but did not provide medications or coronary devices | Unrestricted grants from the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (grant 2013-3), Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific |

|

| Follow-up (months) | 15 (monthly from 3rd month) | 12 | 12 | 24 (landmark analysis at 1 and 12 months) |

| S-DAPT | 3 months DAPT regimen with aspirin 81–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimens, either aspirin 81–200 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or prasugrel 3.75 mg daily, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy | 3 months DAPT regimens, either aspirin 100 mg daily and clopidogrel 175 mg daily or prasugrel 10 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimen with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by 23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy |

| DAPT | 15 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimens with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months |

| Inclusion criteria | Must meet one of the following:

| Patients who underwent successful PCI with CoCr-EES (DES) |

|

|

Must meet one of the following:

| ||||

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3555 vs. 3564 | 1500 vs. 1509 | 1495 vs. 1498 | 7980 vs. 7988 |

| Location | Austria, Canada, China, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Poland, Spain, UK, USA | Japan | Korea | Canada, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, UK, Denmark, Poland, Germany, Brazil, Australia, Singapore, Bulgaria |

| Study design | Randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Randomized, multicentre, open label, adjudicator-blinded clinical trial | Randomized, investigator-initiated, multicentre, open label, non-inferiority | Randomized, open label, superiority trial, multicentre, multinational |

| Funding | Sponsored by Icahn School of Medicine, investigator-initiated grant from AstraZeneca | Abbott Vascular funded the study but did not provide medications or coronary devices | Unrestricted grants from the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (grant 2013-3), Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific |

|

| Follow-up (months) | 15 (monthly from 3rd month) | 12 | 12 | 24 (landmark analysis at 1 and 12 months) |

| S-DAPT | 3 months DAPT regimen with aspirin 81–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimens, either aspirin 81–200 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or prasugrel 3.75 mg daily, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy | 3 months DAPT regimens, either aspirin 100 mg daily and clopidogrel 175 mg daily or prasugrel 10 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor monotherapy | 1-month DAPT regimen with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily followed by 23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy |

| DAPT | 15 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel | 12 months DAPT regimen with aspirin and clopidogrel or prasugrel or ticagrelor | 12 months DAPT regimens with aspirin 75–100 mg daily and clopidogrel 75 mg daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months |

| Inclusion criteria | Must meet one of the following:

| Patients who underwent successful PCI with CoCr-EES (DES) |

|

|

Must meet one of the following:

| ||||

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

Clinical and procedural characteristics were reported in Table 2. Clinical features mainly reflect a real-world population with a mean age of about 65 years old, 80% male with a normal distribution of risk factors. Patients were admitted with an ACS in half of the cases. Left ventricular ejection fraction was not reported in GLOBAL-LEADERS and TWILIGHT, while it was preserved in the other two RCTs. Overall, only one-fourth of cases were performed by femoral access. Angiographic characteristics indicate a higher number of multi-lesion interventions in SMART-CHOICE and GLOBAL-LEADERS (about one-fourth of cases) compared with 6–7% of cases in STOPDAPT-2. Left main PCI ranges from 1.2% to 5.2%, while bifurcation treatment was performed on up to one-fourth of cases. Second generation DES were used in all four studies.

Clinical and procedural features of patients enrolled in the studies

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | |

| Number of patients | 3555 | 3564 | 1500 | 1509 | 1495 | 1498 | 7980 | 7988 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||

| Age, mean (years) | 65.2 | 65.1 | 68.1 | 69.1 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 64.6 |

| Female (%) | 23.8 | 23.9 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 27.3 | 25.8 | 23.4 | 23.1 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 64.0 | 65.7 | 37.7 | 38.6 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| STEMI (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 12.9 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 28.8 | 30.8 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 21.1 | 21.1 |

| UA (%) | 35.1 | 34.9 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Stable CAD (%) | 29.5 | 28 | 62.3 | 61.4 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prior PCI (%) | 42.3 | 42.0 | 33.5 | 35.1 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 32.7 | 32.7 |

| Prior MI (%) | 28.7 | 28.6 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 23.0 | 23.6 |

| Prior stroke (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.6 | 72.2 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 61.6 | 61.3 | 74.0 | 73.3 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 60.7 | 60.2 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 45.1 | 45.5 | 69.3 | 70.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 37.1 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 38.2 | 36.8 | 25.7 | 24.9 |

| CKD (%) | 16.8 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 13.9 | 13.5 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (%) | NA | NA | 59.8 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 59.9 | NA | NA |

| Multivessel disease (%) | 63.9 | 61.6 | NA | NA | 50.1 | 49.0 | NA | NA |

| Procedural features | ||||||||

| Radial access (%) | 73.1 | 72.6 | 82.1 | 83.8 | 73.0 | 72.8 | 73.9 | 74.2 |

| Number of target lesions, mean | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3. |

| Left main coronary artery (%) | 4.7 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Left anterior descending artery (%) | 56.1 | 56.4 | 55.2 | 56.6 | 48.8 | 50.4 | 41.2 | 42 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery (%) | 32.4 | 32.2 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 24.5 |

| Right coronary artery (%) | 35.0 | 35.3 | 29.1 | 27.2 | 28.3 | 27.8 | 31.6 | 30.7 |

| Multilesion intervention (%) | NA | NA | 6.7 | 7.7 | 28.8 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 25.3 |

| Bifurcation lesion (%) | 12.2 | 12.1 | 25.1 | 26.0 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| Calcified lesion (%) | 14.0 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.3 | NA | NA |

| Number of implanted stents, mean | NA | NA | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Minimal stent diameter, mean (mm) | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.96 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Total stent length, mean (mm) | 40.1 | 39.7 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 38.0 | 37.8 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| Second generation DESa | 97.8 | 97.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Cobalt–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | 35.1 | 35.1 | NA | NA |

| Platinum–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 31.9 | NA | NA |

| Sirolimus-eluting with biodegradable polymer (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.2 | 32.8 | NA | NA |

| Biolimus A9-eluting stent (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Antiplatelet regimen | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet adherence (%) | 87.1 | 85.9 | 90 | 56.2 | 79.3 | 95.5 | 81.7 | 89.3 |

| Aspirin (%) | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Clopidogrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 60.2 | 62.9 | 76.9 | 77.6 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prasugrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.6 | 37 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ticagrelor (%) | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 17.9 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | |

| Number of patients | 3555 | 3564 | 1500 | 1509 | 1495 | 1498 | 7980 | 7988 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||

| Age, mean (years) | 65.2 | 65.1 | 68.1 | 69.1 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 64.6 |

| Female (%) | 23.8 | 23.9 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 27.3 | 25.8 | 23.4 | 23.1 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 64.0 | 65.7 | 37.7 | 38.6 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| STEMI (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 12.9 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 28.8 | 30.8 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 21.1 | 21.1 |

| UA (%) | 35.1 | 34.9 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Stable CAD (%) | 29.5 | 28 | 62.3 | 61.4 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prior PCI (%) | 42.3 | 42.0 | 33.5 | 35.1 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 32.7 | 32.7 |

| Prior MI (%) | 28.7 | 28.6 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 23.0 | 23.6 |

| Prior stroke (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.6 | 72.2 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 61.6 | 61.3 | 74.0 | 73.3 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 60.7 | 60.2 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 45.1 | 45.5 | 69.3 | 70.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 37.1 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 38.2 | 36.8 | 25.7 | 24.9 |

| CKD (%) | 16.8 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 13.9 | 13.5 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (%) | NA | NA | 59.8 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 59.9 | NA | NA |

| Multivessel disease (%) | 63.9 | 61.6 | NA | NA | 50.1 | 49.0 | NA | NA |

| Procedural features | ||||||||

| Radial access (%) | 73.1 | 72.6 | 82.1 | 83.8 | 73.0 | 72.8 | 73.9 | 74.2 |

| Number of target lesions, mean | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3. |

| Left main coronary artery (%) | 4.7 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Left anterior descending artery (%) | 56.1 | 56.4 | 55.2 | 56.6 | 48.8 | 50.4 | 41.2 | 42 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery (%) | 32.4 | 32.2 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 24.5 |

| Right coronary artery (%) | 35.0 | 35.3 | 29.1 | 27.2 | 28.3 | 27.8 | 31.6 | 30.7 |

| Multilesion intervention (%) | NA | NA | 6.7 | 7.7 | 28.8 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 25.3 |

| Bifurcation lesion (%) | 12.2 | 12.1 | 25.1 | 26.0 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| Calcified lesion (%) | 14.0 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.3 | NA | NA |

| Number of implanted stents, mean | NA | NA | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Minimal stent diameter, mean (mm) | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.96 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Total stent length, mean (mm) | 40.1 | 39.7 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 38.0 | 37.8 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| Second generation DESa | 97.8 | 97.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Cobalt–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | 35.1 | 35.1 | NA | NA |

| Platinum–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 31.9 | NA | NA |

| Sirolimus-eluting with biodegradable polymer (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.2 | 32.8 | NA | NA |

| Biolimus A9-eluting stent (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Antiplatelet regimen | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet adherence (%) | 87.1 | 85.9 | 90 | 56.2 | 79.3 | 95.5 | 81.7 | 89.3 |

| Aspirin (%) | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Clopidogrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 60.2 | 62.9 | 76.9 | 77.6 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prasugrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.6 | 37 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ticagrelor (%) | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 17.9 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

Second generation DES: durable polymer cobalt chromium everolimus eluting stent (EES), durable polymer platinum chromium EES, durable polymer zotarolimus eluting stent, durable polymer cobalt chromium sirolimus eluting stent, biodegradable polymer DES, polymer free DES, bioresorbable vascular scaffold, sirolimus eluting self-apposing stent, and Tacrolimus eluting Carbostent. NA, not available.

Clinical and procedural features of patients enrolled in the studies

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | |

| Number of patients | 3555 | 3564 | 1500 | 1509 | 1495 | 1498 | 7980 | 7988 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||

| Age, mean (years) | 65.2 | 65.1 | 68.1 | 69.1 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 64.6 |

| Female (%) | 23.8 | 23.9 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 27.3 | 25.8 | 23.4 | 23.1 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 64.0 | 65.7 | 37.7 | 38.6 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| STEMI (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 12.9 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 28.8 | 30.8 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 21.1 | 21.1 |

| UA (%) | 35.1 | 34.9 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Stable CAD (%) | 29.5 | 28 | 62.3 | 61.4 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prior PCI (%) | 42.3 | 42.0 | 33.5 | 35.1 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 32.7 | 32.7 |

| Prior MI (%) | 28.7 | 28.6 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 23.0 | 23.6 |

| Prior stroke (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.6 | 72.2 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 61.6 | 61.3 | 74.0 | 73.3 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 60.7 | 60.2 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 45.1 | 45.5 | 69.3 | 70.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 37.1 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 38.2 | 36.8 | 25.7 | 24.9 |

| CKD (%) | 16.8 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 13.9 | 13.5 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (%) | NA | NA | 59.8 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 59.9 | NA | NA |

| Multivessel disease (%) | 63.9 | 61.6 | NA | NA | 50.1 | 49.0 | NA | NA |

| Procedural features | ||||||||

| Radial access (%) | 73.1 | 72.6 | 82.1 | 83.8 | 73.0 | 72.8 | 73.9 | 74.2 |

| Number of target lesions, mean | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3. |

| Left main coronary artery (%) | 4.7 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Left anterior descending artery (%) | 56.1 | 56.4 | 55.2 | 56.6 | 48.8 | 50.4 | 41.2 | 42 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery (%) | 32.4 | 32.2 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 24.5 |

| Right coronary artery (%) | 35.0 | 35.3 | 29.1 | 27.2 | 28.3 | 27.8 | 31.6 | 30.7 |

| Multilesion intervention (%) | NA | NA | 6.7 | 7.7 | 28.8 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 25.3 |

| Bifurcation lesion (%) | 12.2 | 12.1 | 25.1 | 26.0 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| Calcified lesion (%) | 14.0 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.3 | NA | NA |

| Number of implanted stents, mean | NA | NA | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Minimal stent diameter, mean (mm) | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.96 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Total stent length, mean (mm) | 40.1 | 39.7 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 38.0 | 37.8 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| Second generation DESa | 97.8 | 97.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Cobalt–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | 35.1 | 35.1 | NA | NA |

| Platinum–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 31.9 | NA | NA |

| Sirolimus-eluting with biodegradable polymer (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.2 | 32.8 | NA | NA |

| Biolimus A9-eluting stent (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Antiplatelet regimen | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet adherence (%) | 87.1 | 85.9 | 90 | 56.2 | 79.3 | 95.5 | 81.7 | 89.3 |

| Aspirin (%) | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Clopidogrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 60.2 | 62.9 | 76.9 | 77.6 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prasugrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.6 | 37 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ticagrelor (%) | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 17.9 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | |

| Number of patients | 3555 | 3564 | 1500 | 1509 | 1495 | 1498 | 7980 | 7988 |

| Clinical features | ||||||||

| Age, mean (years) | 65.2 | 65.1 | 68.1 | 69.1 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 64.6 |

| Female (%) | 23.8 | 23.9 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 27.3 | 25.8 | 23.4 | 23.1 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 64.0 | 65.7 | 37.7 | 38.6 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| STEMI (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 12.9 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 28.8 | 30.8 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 21.1 | 21.1 |

| UA (%) | 35.1 | 34.9 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 31.2 | 32.8 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Stable CAD (%) | 29.5 | 28 | 62.3 | 61.4 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prior PCI (%) | 42.3 | 42.0 | 33.5 | 35.1 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 32.7 | 32.7 |

| Prior MI (%) | 28.7 | 28.6 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 23.0 | 23.6 |

| Prior stroke (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.6 | 72.2 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 61.6 | 61.3 | 74.0 | 73.3 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 60.7 | 60.2 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 45.1 | 45.5 | 69.3 | 70.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 37.1 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 38.2 | 36.8 | 25.7 | 24.9 |

| CKD (%) | 16.8 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 13.9 | 13.5 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (%) | NA | NA | 59.8 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 59.9 | NA | NA |

| Multivessel disease (%) | 63.9 | 61.6 | NA | NA | 50.1 | 49.0 | NA | NA |

| Procedural features | ||||||||

| Radial access (%) | 73.1 | 72.6 | 82.1 | 83.8 | 73.0 | 72.8 | 73.9 | 74.2 |

| Number of target lesions, mean | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3. |

| Left main coronary artery (%) | 4.7 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Left anterior descending artery (%) | 56.1 | 56.4 | 55.2 | 56.6 | 48.8 | 50.4 | 41.2 | 42 |

| Left circumflex coronary artery (%) | 32.4 | 32.2 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 24.5 |

| Right coronary artery (%) | 35.0 | 35.3 | 29.1 | 27.2 | 28.3 | 27.8 | 31.6 | 30.7 |

| Multilesion intervention (%) | NA | NA | 6.7 | 7.7 | 28.8 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 25.3 |

| Bifurcation lesion (%) | 12.2 | 12.1 | 25.1 | 26.0 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| Calcified lesion (%) | 14.0 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.3 | NA | NA |

| Number of implanted stents, mean | NA | NA | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Minimal stent diameter, mean (mm) | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.96 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Total stent length, mean (mm) | 40.1 | 39.7 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 38.0 | 37.8 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| Second generation DESa | 97.8 | 97.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Cobalt–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | 35.1 | 35.1 | NA | NA |

| Platinum–chromium everolimus eluting (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 31.9 | NA | NA |

| Sirolimus-eluting with biodegradable polymer (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.2 | 32.8 | NA | NA |

| Biolimus A9-eluting stent (%) | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| Antiplatelet regimen | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet adherence (%) | 87.1 | 85.9 | 90 | 56.2 | 79.3 | 95.5 | 81.7 | 89.3 |

| Aspirin (%) | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Clopidogrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 60.2 | 62.9 | 76.9 | 77.6 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| Prasugrel (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.6 | 37 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ticagrelor (%) | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 17.9 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

Second generation DES: durable polymer cobalt chromium everolimus eluting stent (EES), durable polymer platinum chromium EES, durable polymer zotarolimus eluting stent, durable polymer cobalt chromium sirolimus eluting stent, biodegradable polymer DES, polymer free DES, bioresorbable vascular scaffold, sirolimus eluting self-apposing stent, and Tacrolimus eluting Carbostent. NA, not available.

Antiplatelet adherence was reported in all studies: at 1-year follow-up, it ranged from 79% to 95% in all groups except the DAPT arm in STOPDAPT-2 where it was 56%.

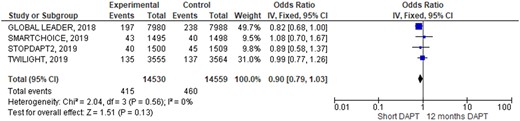

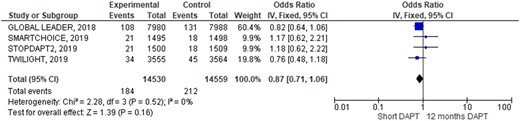

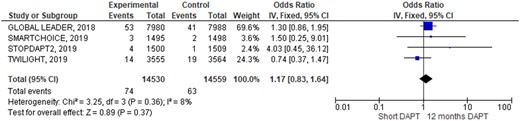

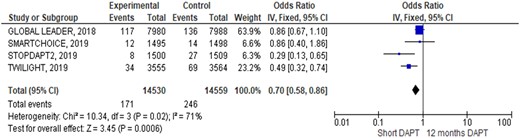

Outcomes occurrence in each individual study was summarized in Table 3. At pooled analysis, MACCE rate was similar (OR 0.90; 95% CIs 0.79–1.03, Figure 2) as well as any of its composites: all causes of death (OR 0.87; 95% CIs 0.71–1.06, Figure 3), myocardial infarction (OR 1.06; 95% CIs 0.90–1.26, Supplementary material online, Figure SA), and stroke (OR 1.12; 95% CIs 0.82–1.53, Supplementary material online, Figure SB). Similarly, also definite/probable ST rate was similar in the two groups (OR 1.17; 95% CIs 0.83–1.64, Figure 4). Conversely, BARC 3 or 5 bleeding resulted significantly lower adopting an S-DAPT strategy (OR 0.70; 95% CIs 0.58–0.86, Figure 5). Random-effects analysis showed similar results (Supplementary material online, Figure SE). Risk of bias of included RCTs (evaluated both with JADAD scale and Cochrane) was low, especially regarding randomization and selection bias (Supplementary material online, Appendix Figure SC and Appendix Table SA). Funnel plots analysis did not show relevant publication bias (Supplementary material online, Appendix Figure D). Egger’s test was not significant (P = 0.72).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, or stroke during 1-year follow-up.

Rates of definite or probable stent thrombosis during 1-year follow-up.

Endpoints of interest up to 12 months

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (Cis) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | |

| MACCE (all cause of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke; %) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 2.80 | 2.97 | NA | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.4 (−∞ to 1.3)a | 2.47 | 2.98 | 0·83 (0·69–1·00) |

| Death from any cause (%) | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.35 | 1.64 | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) |

| MI (%) | 2.70 | 2.70 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.19 (0.54–2.67) | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.66 (0.31–1.40) | 2.24 | 1.98 | 1.14 (0.92–1.41) |

| Stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) (%) | 0.50 | 0.20 | 2.00 (0.86–4.67) | 0.54 | 1.09 | 0.50 (0.22–1.18) | 0.80 | 0.30 | 2.23 (0.78–6.43) | 0.65 | 0.61 | 1.07 (0.72–1.57) |

| Stent thrombosis (definite or probable; %) | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.74 (0.37–1.47) | 0.27 | 0.07 | 4.03 (0.45–36.08) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.51 (0.25–9.02) | 0.66 | 0.51 | 1.30 (0.86–1.95) |

| BARC type 3 or 5 (%) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.54 | 1.81 | 0.30 (0.13–0.65) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.40–1.88) | 1.47 | 1.70 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) |

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (Cis) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | |

| MACCE (all cause of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke; %) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 2.80 | 2.97 | NA | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.4 (−∞ to 1.3)a | 2.47 | 2.98 | 0·83 (0·69–1·00) |

| Death from any cause (%) | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.35 | 1.64 | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) |

| MI (%) | 2.70 | 2.70 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.19 (0.54–2.67) | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.66 (0.31–1.40) | 2.24 | 1.98 | 1.14 (0.92–1.41) |

| Stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) (%) | 0.50 | 0.20 | 2.00 (0.86–4.67) | 0.54 | 1.09 | 0.50 (0.22–1.18) | 0.80 | 0.30 | 2.23 (0.78–6.43) | 0.65 | 0.61 | 1.07 (0.72–1.57) |

| Stent thrombosis (definite or probable; %) | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.74 (0.37–1.47) | 0.27 | 0.07 | 4.03 (0.45–36.08) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.51 (0.25–9.02) | 0.66 | 0.51 | 1.30 (0.86–1.95) |

| BARC type 3 or 5 (%) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.54 | 1.81 | 0.30 (0.13–0.65) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.40–1.88) | 1.47 | 1.70 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) |

Estimate of difference, % (95% one-sided CI). NA, not available.

Endpoints of interest up to 12 months

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (Cis) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | |

| MACCE (all cause of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke; %) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 2.80 | 2.97 | NA | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.4 (−∞ to 1.3)a | 2.47 | 2.98 | 0·83 (0·69–1·00) |

| Death from any cause (%) | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.35 | 1.64 | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) |

| MI (%) | 2.70 | 2.70 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.19 (0.54–2.67) | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.66 (0.31–1.40) | 2.24 | 1.98 | 1.14 (0.92–1.41) |

| Stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) (%) | 0.50 | 0.20 | 2.00 (0.86–4.67) | 0.54 | 1.09 | 0.50 (0.22–1.18) | 0.80 | 0.30 | 2.23 (0.78–6.43) | 0.65 | 0.61 | 1.07 (0.72–1.57) |

| Stent thrombosis (definite or probable; %) | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.74 (0.37–1.47) | 0.27 | 0.07 | 4.03 (0.45–36.08) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.51 (0.25–9.02) | 0.66 | 0.51 | 1.30 (0.86–1.95) |

| BARC type 3 or 5 (%) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.54 | 1.81 | 0.30 (0.13–0.65) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.40–1.88) | 1.47 | 1.70 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) |

| . | TWILIGHT, N Engl J Med 2019 . | STOPDAPT-2, JAMA 2019 . | SMART-CHOICE, JAMA 2019 . | GLOBAL LEADERS, Lancet 2018 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (Cis) . | S-DAPT . | DAPT . | HR (CIs) . | |

| MACCE (all cause of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke; %) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 2.80 | 2.97 | NA | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.4 (−∞ to 1.3)a | 2.47 | 2.98 | 0·83 (0·69–1·00) |

| Death from any cause (%) | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.18 (0.63–2.21) | 1.35 | 1.64 | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) |

| MI (%) | 2.70 | 2.70 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 0.88 | 0.75 | 1.19 (0.54–2.67) | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.66 (0.31–1.40) | 2.24 | 1.98 | 1.14 (0.92–1.41) |

| Stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) (%) | 0.50 | 0.20 | 2.00 (0.86–4.67) | 0.54 | 1.09 | 0.50 (0.22–1.18) | 0.80 | 0.30 | 2.23 (0.78–6.43) | 0.65 | 0.61 | 1.07 (0.72–1.57) |

| Stent thrombosis (definite or probable; %) | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.74 (0.37–1.47) | 0.27 | 0.07 | 4.03 (0.45–36.08) | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.51 (0.25–9.02) | 0.66 | 0.51 | 1.30 (0.86–1.95) |

| BARC type 3 or 5 (%) | 1.00 | 2.00 | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.54 | 1.81 | 0.30 (0.13–0.65) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.40–1.88) | 1.47 | 1.70 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) |

Estimate of difference, % (95% one-sided CI). NA, not available.

Discussion

The main finding of the present meta-analysis is the absence of MACCE increase in patients interrupting aspirin in the first 3 months after a PCI for stable CAD or ACS compared to those continuing DAPT for 12 months. The second most important finding is the significant reduction in clinically relevant bleeding in patients in which aspirin therapy is interrupted after the first 3 months.

The first datum seems directly connected to the very low adverse events rate connected to second and third generation DES.18,19 The low thrombogenicity of new devices could allow a less intense antiplatelet therapy shortly after their implantation and the previously demonstrated superiority of P2Y12i over aspirin in preventing platelet aggregation make the ADP signalling pathway the preferred target to block when one of the two antiplatelet therapies is interrupted. Even the CAPRIE study, in a pre-stent era, had already shown similar results.20,21 The results of our meta-analysis seem to support these observations and potentially they open the field to P2Y12i monotherapy after the first 3 months of DAPT in patients treated with current DES. Notably, the pooled analysis of data highlights an overall significant difference in terms of BARC 3 or 5 bleedings between patients treated with short vs. standard DAPT. Nevertheless, due to the absence of studies with similar design, testing the hypothesis of early interrupting P2Y12i and continuing aspirin, we do not know if aspirin would have led to similar results. In our opinion, previous data showing a high incidence of aspirin sub-optimal response in patients with diabetes and the potentially detrimental effects of prostacyclin inhibition connected to aspirin use on top of P2Y12i therapy make this way less practicable.22–24

In order to clarify if a strategy of early aspirin interruption is ready for ‘prime time’, five sub-studies of the GLOBAL LEADERS Trial were recently published, further analysing data from this study: the GLOBAL LEADERS Adjudication Sub-Study (GLASSY),25 a post hoc analysis of ACS patients,26 a post hoc analysis in patients with long stenting 27 a post hoc analysis in patients who underwent complex PCI,28 and finally a post hoc analysis of patients >75 years old.29

In the GLASSY pre-specified sub-study, considering also potential unreported event triggers in the 20 highest recruiting sites, at 2 years the S-DAPT strategy (1-month DAPT followed by 23-month Ticagrelor alone) resulted non-inferior to conventional treatment for efficacy (all causes of death, non-fatal MI/stroke or urgent target vessel revascularization) but did not reach superiority as well as for safety (no reduction in BARC 3 or 5 bleedings). The post hoc analysis by Tomaniak et al. examined 1- to 12-month clinical outcomes in the ACS population of the Trial, aiming to clarify the impact of aspirin in the context of a more potent P2Y12 antagonist; it showed a significant increase of bleeding risk for conventional post-ACS DAPT (aspirin plus Ticagrelor) compared to Ticagrelor alone, with no additional benefit in terms of reduction of ischaemic events. These outcomes, somehow comparable with those of the TWILIGHT, strongly support the results of our meta-analysis. One more ongoing study is currently exploring the topic of S-DAPT with aspirin discontinuation in ACS patients, the TICO study.30 The TICO randomized open-label trial evaluated whether ticagrelor monotherapy following 3-month DAPT was superior to 12-month ticagrelor-based DAPT in terms of net adverse clinical events (NACE) including efficacy and safety in ACS patients treated with ultrathin bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents. It enrolled 3056 subjects in Korea and showed a significant reduction of NACE in ticagrelor monotherapy group driven by a reduced risk of TIMI major bleeding without differences in ischaemic events. However, this study had several limitations. Firstly, overall event rates were lower than anticipated and the trial was powered for the NACE composite outcome making comparisons of ischaemic events underpowered. Secondly, patients at high bleeding risk were excluded and the results cannot be extrapolated to this group of patients commonly treated with stenting in everyday practice.31 Thus, future information on ACS all-comers patients treated with contemporary DES remains of paramount importance because in this setting the coexistence of high bleeding and high thrombotic risk is very common and the needs of optimize the treatment the greatest.

Two post hoc analysis of the GLOBAL LEADERS evaluated patients undergoing complex PCI on the basis of the definition of the ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularization (containing at least one of the following characteristics: multivessel PCI, ≥3 stents implanted, ≥3 lesions treated, bifurcation PCI with ≥2 stents, or total stent length >60 mm) or long stenting.27,28,32 Both the studies showed that ticagrelor monotherapy after first month DAPT could balance ischaemic and bleeding risk in patients undergoing complex PCI or with stent length >46 mm. The TWILIGHT study including in the same way patients undergoing complex PCI showed similar results. In particular, the recently published TWILIGHT-COMPLEX study33 reported about 2342 patients enrolled in TWILIGHT that met the criteria for complex PCI defined as: three vessels or three or more lesions treated, total stent length greater than 60 mm, bifurcation with two stents implanted, atherectomy device use, left main PCI, surgical bypass graft, or chronic total occlusion as target lesions. Results of the analysis showed a significantly lower rates of BARC 2, 3, or 5 bleeding (<0.0001), and BARC 3 or 5 type bleeding in patients treated with ticagrelor alone compared to ticagrelor plus aspirin (P = 0.009) without differences in any ischaemic outcomes. In our opinion, these results are very interesting and, in the future, could allow aspirin being stopped early in patients with concomitant high ischaemic and bleeding risk like elderly patients.

Finally, three major questions remain unsolved: which is the best P2Y12i in the context of S-DAPT after PCI? Is it possible to safely interrupt aspirin before 1 month? Which medications should be continued after 12 months?

Outcomes stratified on the basis of different P2Y12i were not available for the studies included in our meta-analysis. Ticagrelor is the most studied P2Y12i in this context at the moment but future studies, like the ASET trial could contribute to understand if also prasugrel is a good option for S-DAPT after PCI.34 Moreover, the ASET trial will be the first study trying to understand if aspirin can be interrupted even before 1 month in stable CAD patients undergoing PCI. Dedicated study to understand which is the best antiplatelet therapy after 12 months would be welcome in order to provide an answer to this very important question.

Limitations

As in any meta-analysis, our study is subject to the limitations and the design of the selected studies. Firstly, the four studies include different P2Y12i and in two cases the S-DAPT protocol contemplates a 3-month DAPT vs. 1-month in the other two studies. This does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the safety of a 1-month interruption. Moreover, due to the different P2Y12i used and the absence of endpoints for each of them, it is not possible to say if the safety and efficacy of early aspirin interruption is a class effect or if it is present only for more potent P2Y12i.

Secondly, two of the four studies included were conducted in East Asia, introducing a potential confounder related to ethnicity. This potential bias is mitigated by the fact that most of the patients included in the analysis come from wide international studies.

Thirdly, separate results for particular subgroups such as ACS patients were not available in the considered studies as dedicated subgroup analysis was not possible in our meta-analysis. However, a non-prespecified, post hoc analysis of the GLOBAL LEADERS among ACS patients explored this topic showing that, between 1 month and 12 months after PCI, aspirin was associated with increased bleeding risk and appeared not to add to the benefit of ticagrelor on ischaemic events.26

Moreover, due to the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the studies considered, our results cannot be fully generalized. In particular, a very low percentage of STEMI patients were included and the TWILIGHT study even excluded them. For these reasons, an S-DAPT strategy for such patients does not appear sufficiently supported by data at the moment.

Finally, in the authors’ opinion, the topic addressed by the present meta-analysis is particularly complex and the intrinsic limitations of the meta-analytic methods do not allow a general conclusion to be reached for all the wide range of clinical presentation of CAD patients.

Conclusions

After a PCI with current DES, an S-DAPT strategy followed by P2Y12i monotherapy in patients without STEMI, was associated with a lower incidence of clinically relevant bleeding compared to standard DAPT duration without significant differences in terms of 1-year cardiovascular events. Further studies evaluating patients with different clinical characteristics of those included in the recent RCTs are required to draw definitive conclusions on safety and efficacy of early aspirin interruption followed by P2Y12i monotherapy after PCI.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy online.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Michael Andrews for his valuable contribution to the English revision.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

Presented by Dr. Byeong-Keuk Kim at the American College of Cardiology Virtual Annual Scientific Session Together With World Congress of Cardiology (ACC 2020/WCC), 30 March,

Author notes

Website: Cardiogroup.org.