Abstract

Infants are at a higher risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related hospitalizations compared to older children. In this study, we investigated the effect of the recommended third maternal dose of BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy on rates of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations. We conducted a nationwide cohort study of all live-born infants delivered in Israel between 24 August 2021 and 15 March 2022 to estimate the effectiveness of the third booster dose versus the second dose against infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Data were analyzed for the overall study period, and the Delta and Omicron periods were analyzed separately. Cox proportional hazard regression models estimated hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for infant hospitalizations according to maternal vaccination status at delivery. Among 48,868 live-born infants included in the analysis, rates of COVID-19 hospitalization were 0.4%, 0.6% and 0.7% in the third-dose, second-dose and unvaccinated groups, respectively. Compared to the second dose, the third dose was associated with reduced infant hospitalization with estimated effectiveness of 53% (95% CI: 36–65%). Greater protection was associated with a shorter interval between vaccination and delivery. A third maternal dose during pregnancy reduced the risk of infant hospitalization for COVID-19 during the first 4 months of life, supporting clinical and public health guidance for maternal booster vaccination to prevent infant COVID-19 hospitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Infants are at increased risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related hospitalizations, including acute respiratory failure, compared to older children1,2,3. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) records, hospitalization rates of infants younger than 6 months of age were approximately six times higher during the peak week of Omicron predominance compared to Delta predominance1. During the Omicron period, hospitalizations of infants younger than 6 months of age accounted for 44% of all infants and children with COVID-19 hospitalization, aged 0–4 years, mostly without underlying medical conditions1. Although mRNA vaccines were recently authorized for children as young as 6 months of age4,5, prevention of infection and illness for younger infants remains an issue of major concern.

Maternal immunization during pregnancy may provide the benefit of vertical immunity to the fetus via the transplacental passage of immunoglobulins6,7,8. Previous data show that maternal immunization during pregnancy prevents pertussis and influenza infections in early infancy9,10,11, but there is little evidence on the effect of maternal immunization against COVID-19 on infant morbidity. Halasa et al.12 found an association between maternal vaccination with the second dose of mRNA vaccine and reduced risk of COVID-19-related hospitalizations and critical disease among infants younger than 6 months of age. This protective effect was highest if the second dose of vaccine was administered after 20 weeks’ gestation.

We previously described the robust maternal humoral immune response to COVID-19 vaccination, coupled with a rise in neutralizing anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies in the fetal circulation13. We further showed that a third booster dose of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine augmented maternal and neonatal humoral immunity, beyond that achieved with the second dose regimen14,15. After delivery, levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 protective antibodies gradually drop during the first 4 months of life16,17,18. Nevertheless, protective effect may last up to 4 months after birth, as was demonstrated in a large Norwegian population-based cohort study, where vaccination during pregnancy was associated with significantly lower incidence of infant SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to unvaccinated mothers19.

The third boosting dose of COVID-19 vaccination is currently recommended for pregnant women20,21. In Israel, the recommendation for a third vaccine dose in pregnant women was announced in August 2021, concomitantly with the surge of the Delta variant. To be eligible for a third dose, women had to have received their second dose at least 5 months earlier. Evidence on the effect of maternal third dose on the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalizations in their infants is lacking. We, therefore, studied the association of maternal immunization with three doses versus two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 administered at least 5 months earlier and the incidence of infant hospitalizations during their first 4 months of life.

Results

Participants

During the study period, 48,868 infants met the eligibility criteria. In total, 22,231 (45.5%) infants were born to mothers who received three vaccine doses (third-dose group); 13,364 (27.3%) infants were born to mothers who received two doses and were eligible but did not receive a third vaccine and at least 5 months had elapsed since they received their second dose (second-dose group); and 13,273 (27.2%) infants were born to unvaccinated mothers (unvaccinated group) (Fig. 1). Among the vaccinated cohort (second-dose and third-dose groups), 57.2% received their second vaccine before pregnancy. Among the third-dose group, all mothers received the third dose during pregnancy except two individuals who received it before pregnancy. The proportion of infants born to mothers who received the third dose increased during the study period (Extended Data Fig. 1).

The flow chart shows the three comparison groups investigated during the study periods. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.

Characteristics of infants in this study are presented in Table 1. The largest maternal age stratum in the study was 27–35 years, n = 26,864 (55.0%), followed by ≤26 years, n = 12,057 (24.7%), and ≥36 years, n = 9,748 (19.9%). Mothers of infants in the third-dose group were older (23.8% in the 36–45-years age group) compared to the second dose and unvaccinated groups (17.6% and 16.2%, respectively). Grand multiparity (parity ≥5) was more common among the unvaccinated group (17.9%) than the third-dose (9.0%) and second-dose (10.1%) groups. Incidence of preterm deliveries and low birthweight did not differ among the groups (P = 0.736 and P = 0.078, respectively).

Incidence of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations

A total of 352 (0.72%) infants up to the age of 120 days were hospitalized for COVID-19 during the study period. Eighty-nine infants who were hospitalized for reasons other than COVID-19 but were found to coincidentally test positive for SARS-CoV-2 were not included in the study outcome (see Extended Data Table 1, which summarizes the main medical conditions). The remaining 263 (75%) infants were included in further analyses. Figure 2a shows the number of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations during the study period (24 August 2021 to 15 March 2022) for all study groups. Infants of mothers who received a third dose had a lower (0.4%) incidence of COVID-19-related hospitalizations compared to infants of mothers who received a second dose only (0.6%; P < 0.001) or unvaccinated mothers (0.7%; P < 0.001) (Table 1, lower panel). Similar differences were observed when calculating cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related hospitalizations among study groups (log-rank P < 0.001; Fig. 2b).

a, Number of infant COVID-19 hospitalizations among the study cohort, between 24 August 2021 and 15 March 2022. b, Cumulative incidence plot of infant COVID-19 hospitalizations, up to 120 days after delivery, by maternal vaccination status (study group). Shaded areas represent 95% CIs. The center line represents the cumulative number of events at each timepoint. The number at risk at each timepoint and the cumulative number of events are also shown for each outcome.

Severity of COVID-19 in hospitalized infants

Among the 263 infants hospitalized due to COVID-19, 15 (5.7%) were born preterm (<37 weeks); 20 (7.6%) were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at the time of delivery; and 15 (5.7%) were diagnosed with major congenital anomalies (including cardiac (n = 10), urinary (n = 1), brain (n = 2) and skeletal (n = 1)), with no statistical differences among the three vaccine groups (P = 0.558, P = 0.669 and P = 0.759, for preterm, NICU and major anomalies, respectively). The median infant age at the time of hospitalization was 47 days (interquartile range, 27–63 days), which was similar for the three study groups (P = 0.262). Infants of mothers who received the third dose had a shorter duration of hospitalizations compared to infants of mothers who were eligible for the third dose but received a second dose only and unvaccinated mothers (means ± s.d.: 1.77 ± 0.90 days versus 2.28 ± 1.32 days and 2.44 ± 1.76 days, respectively; P = 0.005). Overall, a total of ten infants (3.8% of COVID-19-related hospitalizations) were admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with COVID-19, including two infants (2.4%) in the third-dose group, three infants (3.5%) in the second-dose group and five (5.3%) infants in the unvaccinated group (P = 0.603) (Table 1). None of the COVID-19 hospitalizations ended in death, and there were no deaths attributed to COVID-19 in infants during the study period.

Vaccine effectiveness of the third dose

Overall, the hazard ratio (HR) of the third dose versus the second dose administered 5 months or more prior against COVID-19-related infant hospitalization was 0.47 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.35–0.64) with estimated vaccine effectiveness of 53% (95% CI: 36–65), for the first 120 days after delivery. Vaccine effectiveness remained similar when stratified by infant sex and term deliveries and for infants born appropriate for gestational age (AGA) (Fig. 3). The relatively small number of cases (n < 10) for stratification to subgroups (preterm, small for gestational age (SGA) and large for gestational age (LGA)) limited vaccine effectiveness estimation. Similar values of estimated vaccine protection were obtained in analyses comparing the third-dose group with the unvaccinated group. No significant protective effect of vaccination was found when comparing the second-dose group with the unvaccinated group ((−16), 95% CI: −56% to −14%) (Fig. 3).

a, Comparison between the third-dose and second-dose groups. b, Comparison between the third-dose and unvaccinated groups. c, Comparison between the second-dose and unvaccinated groups. Forest plot depicting pregnancy vaccine effectiveness against infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations during the first 120 days of life. Vaccine effectiveness was calculated as (1 − adjusted HR) × 100 of the indicated model. Overall models adjusted for maternal age, parity, gestational age at delivery, infant sex, multifetal pregnancy and birthweight groups. Models of the effect of infant sex stratum were adjusted for maternal age, parity, gestational age at delivery, multifetal pregnancy and birthweight groups. Time of delivery models were adjusted for maternal age, parity, infant sex, multifetal pregnancy and birthweight groups. Birthweight percentile for gestational age group models was adjusted for maternal age, parity, gestational age at delivery, infant sex and multifetal pregnancy. Error bars represent the median and 95% CI. Dotted line shows no effect point. *Missing data: one infant in the unvaccinated group was not assigned sex at birth, and 91 infants (33 in the third-dose group, 30 in the second-dose group and 28 in the unvaccinated group) were missing birthweight.

Protection over time after delivery

Studying the protection of the third dose in 30-day intervals after birth, the third dose was more effective than the second dose in preventing hospitalization in infants at the first 90 days of life (HR= 0.41 (95% CI: 0.22–0.78), HR = 0.45 (95% CI: 0.28–0.72) and HR = 0.53 (95% CI: 0.30–0.95), for 0–29 days, 30–59 days and 60–89 days, respectively), whereas it had no additional protection beyond 90 days (HR = 0.69 (95% CI: 0.11–4.16) (Fig. 4a)).

a, Adjusted HR for infant COVID-19 hospitalization in the third-dose group compared to the second-dose group, calculated per 30-day intervals and plotted by time from delivery (the lower the HR, the greater the protection conferred). Error bars represent 95% CI of the adjusted HR for each infant age group; the center line represents the median, and the dotted line shows no effect point. The infant age strata of 0–29 days, 30–59 days, 60–89 days and 90–119 days included n = 35,595, n = 29,141, n = 21,931 and n = 15,017 infants, respectively. b, The timing of infant COVID-19 hospitalization has a significant negative correlation with time elapsed from maternal third vaccination until delivery (Pearson’s r = −0.536, P < 0.001). c, The timing of infant COVID-19 hospitalization has a moderate but significant negative correlation with the time elapsed from maternal last (second) vaccination until delivery (Pearson’s r = −0.322, P = 0.003).

Timing of third vaccination and infant protection

To evaluate how the timing of maternal vaccination affected infant protection, we studied the correlation between the time interval between maternal last vaccination and delivery and infant age at hospitalization. Using Pearsonʼs correlation comparing days from last maternal vaccination and infant age at hospitalization, we found an overall statistically significant negative correlation in the third-dose group (r = −0.536, P < 0.001) and a significant moderate negative correlation in the second-dose group (r = −0.322, P = 0.003) (Fig. 4b,c, respectively), suggesting that longer time elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery was associated with lower protection to infants. Evidence for the waning of third boosting dose protection was also observed in Kaplan–Meier analysis, which showed that shorter interval between maternal third vaccination and delivery (for strata 0–49 days, 50–99 days and 100–149 days) was associated with lower cumulative incidence of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Variants and vaccine effectiveness in the first month of life

We further evaluated the study outcome in the first 30 days of life during the Delta and Omicron periods. During the Delta period (24 August 2021 to 1 December 2021) 16/23,865 (0.07%) infants were hospitalized due to COVID-19. There were no hospitalizations of infants in the third-dose group (0/8,272), 4/7,381 (0.05%) hospitalizations in the second-dose group and 12/8,212 (0.15%) hospitalizations in the unvaccinated group (P = 0.001). During the Omicron wave (15 December 2021 to 15 March 2022), 50/20,893 (0.24%) infants were hospitalized due to COVID-19, with 17/11,745 (0.14%) hospitalizations in the third-dose group, 19/4,905 (0.39%) hospitalizations in the second-dose group and 14/4,243 (0.33%) hospitalizations in the unvaccinated group (P = 0.006). Infants born between the Delta and Omicron waves, from 2 December 2021 to 14 December 2021 (n = 4,110), were not included in these analyses. Cumulative risk curves for infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations during the Delta and Omicron periods are shown in Fig. 5. Significantly lower cumulative incidence rates were found for infants in the third-dose group compared to the second-dose and unvaccinated groups during the Delta period (log-rank P = 0.040 and P = 0.001, respectively) and Omicron period (log-rank P = 0.002 and P = 0.017, respectively). However, there were non-significant differences in cumulative incidence rates between the second-dose group versus the unvaccinated group in the Delta and Omicron periods (log-rank P = 0.117 and P = 0.649, respectively) (Fig. 5). When comparing the third-dose versus the second-dose groups, effectiveness could not be estimated for the Delta period owing to the low number of cases (zero in the third-dose group and four in the second-dose group), while the vaccine effectiveness during the Omicron period was 65% (95% CI: 32–82%).

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence to support the role of maternal booster vaccination to support infant SARS-CoV-2 immunity in the prevention of early infant COVID-19 morbidity. We report a lower incidence rate and shorter duration of early infant COVID-19 hospitalizations among infants of mothers who received a third vaccine dose compared to infants of mothers who received the second dose only, at least 5 months before delivery. We found an association between the timing of the third dose and the timing of infant COVID-19 hospitalization, which supports an advantage of vaccination in the later stages of pregnancy. The protective effect of the third vaccine dose declined over time after delivery. Infants of mothers who were in the second-dose group (at least 5 months from the second dose) were not protected from serious disease, emphasizing the importance of maternal booster vaccination. Together, these findings show how waning of maternal SARS-CoV-2 immunity influences infant health.

To date, most of the data regarding the possible benefits of maternal vaccination on early infant infections come from studies that show efficient transport of protective anti SARS-CoV-2 IgG from the mother to the umbilical cord blood at birth13,14,16,22,23,24,25. Vertical SARS-CoV-2 immunity may explain the observations of reduced risk for COVID-19 in infants during early life in mothers who had third-dose vaccination. These findings corroborate previous reports from the Norwegian population that found an association between maternal vaccination and reduced risk for positive SARS-CoV-2 test during the first 4 months of life19 and data from the United States reporting the associations of maternal vaccination with two doses and reduced risk of infant hospitalizations12. Our data provide additional evidence for the role of the third vaccine dose in protecting against COVID-19-related hospitalizations during early infancy. Unlike these previous studies12,19 that included women at any time after administration of the second dose, we included only vaccinated mothers when 5 months had elapsed from the second dose. This allowed us to isolate the effect of the waning of maternal vaccine protection on the immunity extended to infants. As many women have waning immunity after the second dose, we show that a third-dose booster provides additional protection for their children. We further show an association between the timing of maternal vaccination with the third dose and the timing of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations, suggesting that a booster dose given in later pregnancy would increase infant protection. Nevertheless, determining the appropriate timing for boosting is challenging, as the benefits of maximizing infant protection must be balanced against maternal risks of delaying vaccination, considering the risk of severe maternal COVID-19 during pregnancy.

This study focused on the indirect benefits of vaccine boosting in pregnant mothers for their unvaccinated infants. Our results extend previous data showing how parental vaccination confers protection on children residing in the same household26,27, further highlighting the broad impact of parental vaccination on their children’s health. In the case of vaccination during pregnancy, infant vaccine effects are mediated by two main mechanisms: (1) by passage of antibodies across the placenta during pregnancy and through breast milk for breastfed infants and (2) by direct decrease in the chance of exposure to infective agents resulting from a better-protected mother (reduced vector susceptibility and infectiousness)26,28,29,30. Although we acknowledge the importance of a thorough understanding of the relative contribution of each of these protective components, these data were not available for this study and, therefore, require further investigation in future studies.

We found differences between the COVID-19 periods dominated by the Delta and Omicron variants when comparing the impact of maternal vaccination with a third dose on the rates of infant hospitalization. These findings are in agreement with previous reports in the general population of reduced effectiveness of the current mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 mediated by the Omicron variant31,32. As the Omicron variant is genetically divergent from the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain, for which the BNT162b2 vaccine was tailored, it seems to escape vaccine-mediated protection. These findings emphasize the potency and broad effects of maternal vaccination while highlighting the need to tailor vaccines for novel variants. In this context, future studies should evaluate the association of maternal bivalent boosters with infant hospitalizations, as these vaccines are better tailored against the Omicron variant.

The CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other health organizations currently recommend booster doses for pregnant women as soon as they are eligible, to minimize the risk of severe disease15,33,34. These recommendations are based on information showing that COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy safely protects against severe COVID-19 (refs. 35,36,37,38). Nevertheless, vaccine uptake among pregnant populations has been slow in many societies37,39,40. Our results, showing that vaccines during pregnancy reduce the risk for infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations, in addition to the reduction in previously reported maternal risks, may support women’s decisions to be vaccinated and, thereby, improve vaccination uptake rates among pregnant women41. Moreover, as the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 persists, we anticipate that future guidelines will adopt recommendations for routine COVID-19 booster vaccination during the third trimester16, aiming to reduce early infant morbidity, similar to recommendations for pertussis and influenza prevention42,43,44.

Our study’s strengths include the use of registry data covering the whole Israeli population, with high data completeness. In addition, the high compliance with COVID-19 vaccination campaigns among the pregnant population in Israel provides a large cohort for analysis. Mandatory reporting to the Israeli national registries (Methods) limited potential selection bias and provided detailed data on clinical and sociodemographic variables. In addition, we estimated vaccine effectiveness for different subpopulations and found similar effectiveness, further strengthening the relevance of the findings to infants of diverse backgrounds.

This study has several limitations. It is a real-world observational study; therefore, participants were not randomly selected for vaccination. Patients who declined a boosting dose may vary in demographic or obstetric characteristics from other eligible individuals. Sociodemographic variables were unavailable for this study; therefore, we could not control for those potential confounders. Moreover, groups who received booster vaccination could behave in a more cautious way that may reduce their risk of infection. Although women with previous documentation of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test were excluded from the study, natural and hybrid immunity acquired during the pandemic, which may not have been captured by testing in the community, might have affected the results. These possible sources of bias are challenges in a retrospective study design. To overcome these potential biases, we adjusted data for known confounders, but we acknowledge that other, unaccounted-for group and individual risk factors for severe illness or exposure to the virus could have affected our results. We did not adjust our results for maternal morbidities or COVID-19 severity of the infants during hospitalization (for example, COVID-19 degree of severity); therefore, our results must be interpreted with caution. Also, women were included in the third-dose group from the day they received the booster. It is possible that the level of protective antibodies in the first days after booster vaccination was suboptimal. This may have impacted the results overall (that is, lessened the degree of estimated effectiveness). Nonetheless, the level of protection was found to be higher in the third-dose group compared to the second-dose group (among whom at least 5 months had elapsed from the second dose). Furthermore, the data did not include disease symptoms and allowed only limited assessment of disease severity. Finally, data regarding breastfeeding were not available in this study; therefore, we cannot evaluate the role of breastfeeding in mediating protection.

In conclusion, in this national cohort study, a third boosting dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk, and a shorter duration, of infant hospitalization for COVID-19 during the first 4 months of life compared to mothers who did not receive a booster. Our data provide evidence to support infant protection against serious COVID-19 disease after maternal vaccination with the third dose during pregnancy.

Methods

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by Hadassah Medical Organization’s institutional review board (IRB) (approval 0593-21, 5 September 2021). All records were anonymized at the source; therefore, the IRB waived the need for informed consent for this retrospective study.

Study design

We conducted a population-based nationwide historical cohort study comparing the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalizations among infants born to mothers who received a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (third-dose group); infants born to mothers for whom at least 5 months had elapsed since the second dose, making them eligible for the third dose, but who did not receive it (second-dose group); and infants born to unvaccinated mothers (unvaccinated group).

Study population

The study captured all live-born infants from 22 weeksʼ gestational age delivered in Israel from 24 August 2021, when the third vaccine dose became available to the general population, to 15 March 2022, when public policy changes regarding testing and other restrictions were implemented. We included infants born to unvaccinated mothers and infants born to mothers who were eligible to receive the third vaccine dose during pregnancy (at least 5 months had elapsed since their second vaccine dose). Vaccinations were administered before or during pregnancy. We excluded infants born to mothers with documented SARS-CoV-2 infection before delivery. To control for a possible selection bias by which vaccination is also associated with the willingness to be tested, we also excluded women without any documented SARS-CoV-2 test since the beginning of the pandemic. Finally, infants born to mothers who received vaccines other than BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine were also excluded (see flow chart, Fig. 1).

Data source and organization

Data were extracted from TIMNA, the national research infrastructure for big data, established by the Israel Ministry of Health (MOH) for conducting big data health research. The Israel MOH keeps a registry for COVID-19 that holds data on all laboratory-based SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests, vaccinations and confirmed cases. We analyzed integrated participant-level data maintained by the MOH from three primary sources: the COVID-19 Registry, the National Birth Registry and the National Inpatient Registry (including all diagnoses of hospitalized patients in Israel).

Study outcomes

The study outcome was infant hospitalizations due to COVID-19. Data on dates of admission, discharge and outcome on all hospitalizations with ICD-9 code 07984 (COVID-19 infection) were extracted for all infants up to 120 days of age. A consultant pediatrician (Z.E.S.) reviewed the records of all infants with a diagnosis of COVID-19 during their hospitalization, in a blinded fashion, and determined whether the index hospitalization was indeed related to COVID-19 disease. Infants were followed from birth until COVID-related hospitalization, maternal third dose vaccination after birth (as the study focus on the impact of vaccination during pregnancy and not after delivery), age 120 days or the end of the study period. In a secondary analysis, two time periods were defined according to the dominant variant: the Delta period (24 August 2021 to 1 December 2021) and the Omicron period (15 December 2021 to 15 March 2022). Infants born between the two defined periods, 2–14 December 2021, were not included in this secondary analysis. In these analyses, infant follow-up was defined from birth until COVID-related hospitalization, maternal vaccination, 30 days of age or the end of the study period.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the study population by study group were presented as proportions, medians or means and were evaluated using chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier analyses with a log-rank test were performed for univariate analysis, presenting infant hospitalization by infant age in days. Cox proportional hazard models were created to estimate the HRs and 95% CIs for the study outcome in the third-dose group compared to the second-dose group, controlling for maternal age, parity, gestational age, birthweight categories (≤2,500 g, >2,500–3,999 g and ≥4,000 g) and neonatal sex. Additional models compared the third-dose and second-dose groups to the unvaccinated group, controlling for the same covariates. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as a percentage, defined as (1 − HR) × 100; 95% CIs were calculated similarly, for the entire study period and for the Delta and Omicron periods separately. In addition to vaccine effectiveness evaluation in the entire cohort, Cox regression models were stratified for infant sex, timing of delivery (term: ≥37 weeks; preterm: <37 weeks) and birthweight percentile for gestational age (SGA <10th percentile; LGA ≥90th percentile; and AGA ≥10th percentile and <90th percentile). Correlations between the interval from last maternal vaccine to delivery and timing of infant hospitalizations were analyzed by Pearsonʼs correlation.

Python version 3.7.3 and lifelines version 0.24.14 were used for multivariate survival analyses. The SPSS statistical package for Windows, version 24 (IBM), was used for descriptive and univariate analyses. Two-sided P values ≤0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance in all analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw national-level data are protected and are not available due to data privacy laws. The data that support the findings of this study were provided by the Israel Ministry of Health, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Israel Ministry of Health.

Code availability

The modeling in this study used Python version 3.7.3 and lifelines version 0.24.1, which are freely available, and IBM-SPSS for Windows, version 24. Requests for the statistical code will be considered by the authors on an individual basis and require specific approval by the appropriate authorities of the Israel Ministry of Health. BioRender was used to create Fig. 1.

References

Marks, K. J. et al. Hospitalization of infants and children aged 0–4 years with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 2020–February 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 71, 429–436 (2022).

Hobbs, C. V. et al. Frequency, characteristics and complications of COVID-19 in hospitalized infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 41, e81–e86 (2022).

Cui, X. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Med. Virol. 93, 1057–1069 (2021).

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines for children down to 6 months of age. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-moderna-and-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccines-children#:~:text=Today%2C%20the%20U.S.%20Food%20and,to%206%20months%20of%20age (2022).

Anderson, E. J. et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 vaccine in children 6 months to 5 years of age. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1673–1687 (2022).

Goncalves, G. et al. Transplacental transfer of measles and total IgG. Epidemiol. Infect. 122, 273–279 (1999).

Munoz, F. M. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tetanus diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy in mothers and infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311, 1760–1769 (2014).

Martinez, D. R. et al. Fc characteristics mediate selective placental transfer of IgG in HIV-infected women. Cell 178, 190–201 e111 (2019).

Campbell, H. et al. Review of vaccination in pregnancy to prevent pertussis in early infancy. J. Med. Microbiol. 67, 1426–1456 (2018).

Regan, A. K. & Munoz, F. M. Efficacy and safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy: realizing the potential of maternal influenza immunization. Expert Rev. Vaccines 20, 649–660 (2021).

Marchant, A. et al. Maternal immunisation: collaborating with mother nature. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, e197–e208 (2017).

Halasa, N. B. et al. Maternal vaccination and risk of hospitalization for Covid-19 among infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 109–119 (2022).

Beharier, O. et al. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e150319 (2021).

Nevo, L. et al. Boosting maternal and neonatal humoral immunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection using a single mRNA vaccine dose. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 227, 486e1–486e10 (2022).

Guedalia, J. et al. Effectiveness of a third BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: a national observational study in Israel. Nat. Commun. 13, 6961 (2022).

Rottenstreich, A. et al. Kinetics of maternally derived anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies in infants in relation to the timing of antenatal vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, e274–e279 (2022).

Shook, L. L. et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA 327, 1087–1089 (2022).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Neutralization antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 in an infant born to a mother with COVID-19. Pediatr. Neonatol. 62, 661–663 (2021).

Carlsen, E. Ø. et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants. JAMA Intern. Med. 182, 825–831 (2022).

Allotey, J. et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 370, m3320 (2020).

Di Mascio, D. et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2, 100107 (2020).

Atyeo, C. G. et al. Maternal immune response and placental antibody transfer after COVID-19 vaccination across trimester and platforms. Nat. Commun. 13, 3571 (2022).

Collier, A. Y. et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA 325, 2370–2380 (2021).

Prahl, M. et al. Evaluation of transplacental transfer of mRNA vaccine products and functional antibodies during pregnancy and early infancy. Nat. Commun. 13, 4422 (2022).

Mithal, L. B., Otero, S., Shanes, E. D., Goldstein, J. A. & Miller, E. S. Cord blood antibodies following maternal coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225, 192–194 (2021).

Prunas, O. et al. Vaccination with BNT162b2 reduces transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to household contacts in Israel. Science 375, 1151–1154 (2022).

Hayek, S. et al. Indirect protection of children from SARS-CoV-2 infection through parental vaccination. Science 375, 1155–1159 (2022).

Male, V. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 277–282 (2022).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Tchetgen Tchetgen, E. J. Bounding the infectiousness effect in vaccine trials. Epidemiology 22, 686–693 (2011).

Richterman, A., Meyerowitz, E. A. & Cevik, M. Indirect protection by reducing transmission: ending the pandemic with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 9, ofab259 (2022).

Lauring, A. S. et al. Clinical severity of, and effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against, covid-19 from omicron, delta, and alpha SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States: prospective observational study. BMJ 376, e069761 (2022).

Klein, N. P. et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination in preventing COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalizations among nonimmunocompromised children and adolescents aged 5–17 years—VISION Network, 10 states, April 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 71, 352–358 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnant and recently pregnant people at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/pregnant-people.html (2022).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 Vaccination Considerations for Obstetric–Gynecologic Care. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/covid-19-vaccination-considerations-for-obstetric-gynecologic-care (2023).

Goldshtein, I. et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA 326, 728–735 (2021).

Theiler, R. N. et al. Pregnancy and birth outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 3, 100467 (2021).

Stock, S. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 28, 504–512 (2022).

Barda, N. et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1078–1090 (2021).

Qiu, X., Bailey, H. & Thorne, C. Barriers and facilitators associated with vaccine acceptance and uptake among pregnant women in high income countries: a mini-review. Front. Immunol. 12, 626717 (2021).

Iacobucci, G. Covid-19 and pregnancy: vaccine hesitancy and how to overcome it. BMJ 375, n2862 (2021).

Kilich, E. et al. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15, e0234827 (2020).

Cuningham, W. et al. Optimal timing of influenza vaccine during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir. Virusus 13, 438–452 (2019).

Skoff, T. H. et al. Impact of the US maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination program on preventing pertussis in infants <2 months of age: a case–control evaluation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 1977–1983 (2017).

Nunes, M. C. & Madhi, S. A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy for prevention of influenza confirmed illness in the infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 14, 758–766 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Magda and Richard Hoffman Center for Human Placental Research and the ‘Ofek’ Program of the Hadassah Medical Center. The grantors had no role in the conduct of the study or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., J.G., E.M., Y.S. and O.B. saw the original data, collected it and analyzed it. J.G., M.L., O.B., R.C.-M., G.S. and S.Y. conceived and designed the study. M.L., J.G., O.B., R.C.-M., S.M.C., D.-G.W. and S.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript. R.C.-M., S.Y. and O.B. supervised the study process. O.B. vouches for the data and analysis. E.M. and G.S. combined, anonymized and performed quality control of the MOH data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Enny Paixao, Laura Zambrano, Emily Adhikari and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ming Yang, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

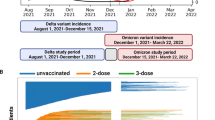

Extended Data Fig. 1 Graphic representation of infant follow-up within the study period, and COVID-19 timeline.

a: Sample of infant follow-up time during the study periods with up to 120 days follow up from delivery. Each row represents an infant, colored by their maternal vaccination status at delivery. Third vaccine (green line), second vaccine (orange line), and unvaccinated (blue line). b: Sample of infant follow-up time during the Delta (on the left side) and Omicron variants (on the right side) periods with up to 30 days follow up from delivery. Each row represents an infant, colored by their maternal vaccination status at delivery. c: Illustration of incidence of infant COVID-19-related hospitalizations within study cohort, between August 24, 2021 and March 15, 2022.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Cumulative incidence plots of COVID-19-related hospitalization, among infants of mothers who received the third boosting dose, stratified by the time elapsed from maternal vaccination to delivery.

The center line represents the cumulative number of events at each time point. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. The number at risk at each time point and the cumulative number of events are also shown for each outcome. Red, 0–49 days; purple, 50–99 days; brown, 100–149 days.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lipschuetz, M., Guedalia, J., Cohen, S.M. et al. Maternal third dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and risk of infant COVID-19 hospitalization. Nat Med 29, 1155–1163 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02270-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02270-2

This article is cited by

-

Maternal hybrid immunity and risk of infant COVID-19 hospitalizations: national case-control study in Israel

Nature Communications (2024)