Abstract

Background: For patients on oral anticoagulants (OAC) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), European guidelines have recently changed their recommendations to dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT; P2Y12 inhibitor and OAC) without aspirin.

Aims: The prospective WOEST 2 registry was designed to obtain contemporary real-world data on antithrombotic regimens and related outcomes after PCI in patients with an indication for OAC.

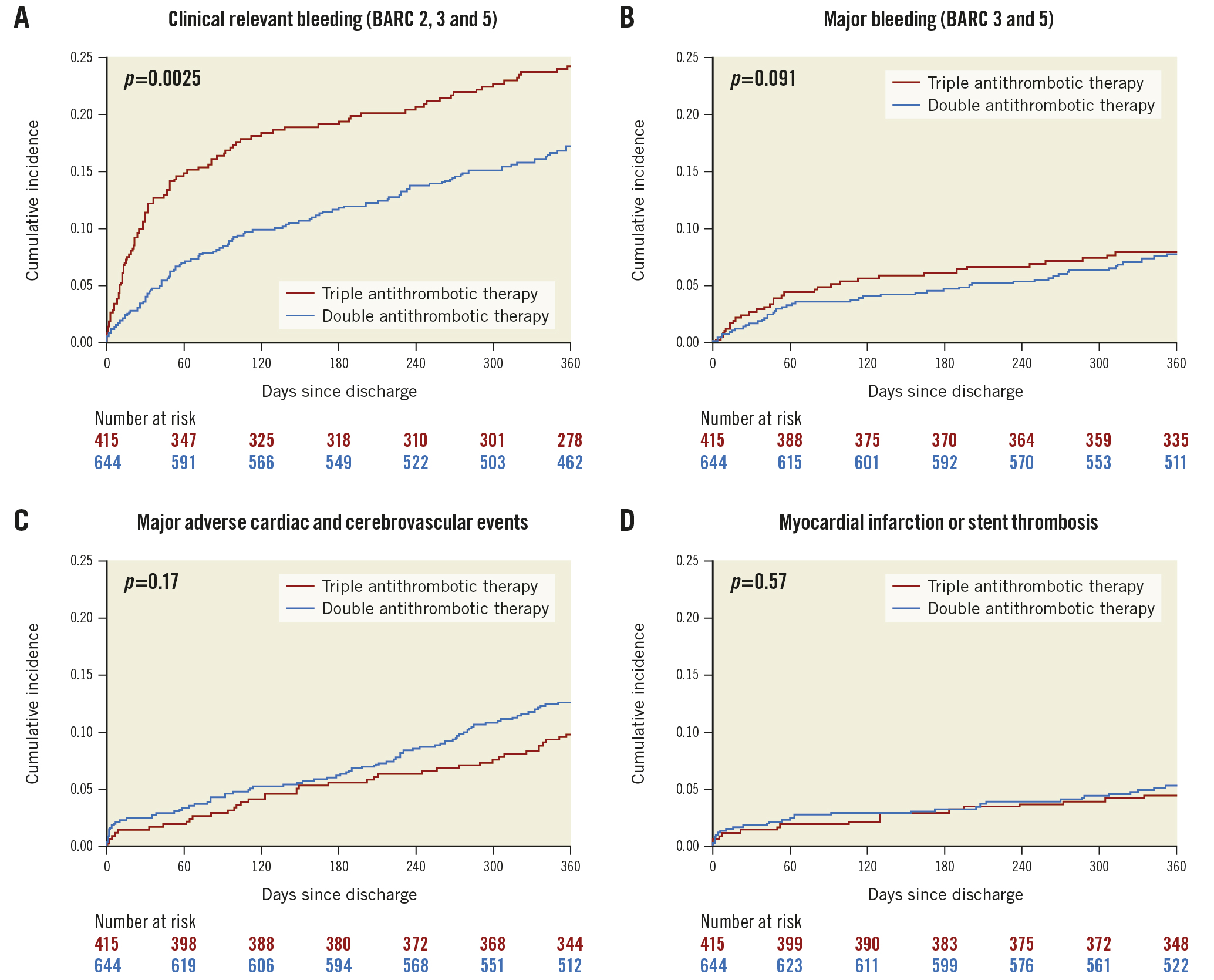

Methods: In this analysis, we compare DAT (P2Y12 inhibitor and OAC) to triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT; aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitor, and OAC) on thrombotic and bleeding outcomes after one year. Clinically relevant bleeding was defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium classification (BARC) grade 2, 3, or 5; major bleeding as BARC grade 3 or 5. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) was defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemic stroke, and transient ischaemic attack.

Results: A total of 1,075 patients were included between 2014 and 2021. Patients used OAC for atrial fibrillation (93.6%) or mechanical heart valve prosthesis (4.7%). Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOAC) were prescribed in 53.1% and vitamin K antagonists in 46.9% of patients. At discharge, 60.9% received DAT, and 39.1% TAT. DAT was associated with less clinically relevant and similar major bleeding (16.8% vs 23.4%; p<0.01 and 7.6% vs 7.7%, not significant), compared to TAT. The difference in MACCE between the two groups was not statistically significant (12.4% vs 9.7%; p=0.17). Multivariable adjustment and propensity score matching confirmed these results.

Conclusions: Dual antithrombotic therapy is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically relevant bleeding without a statistically significant penalty in ischaemic events.

Introduction

Patients with acute coronary syndrome or who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) require dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor to prevent them from myocardial infarction (MI) and stent thrombosis (ST)1. Most patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) require oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy to prevent them from ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism2. Patients with mechanical heart valves require OAC to prevent valve thrombosis3. Coronary artery disease (CAD) frequently co-occurs in patients with AF4 and/or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis5, warranting both DAPT and OAC. Although this combination therapy is effective, it is also accompanied by a high risk of bleeding complications6, which are associated with mortality78. Thus, this combination therapy should be carefully considered910.

The WOEST trial (2013) found an important reduction in bleeding complications for PCI patients on OAC when treated without aspirin, thus treated with dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT, consisting of OAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, also referred to as double antithrombotic therapy; not to be confused with DAPT), when compared to triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT: combination therapy of OAC, P2Y12 inhibitor and aspirin)11. Since then, several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and their meta-analyses have confirmed this result12131415161718. However, dropping aspirin might come at the cost of reduced antithrombotic efficacy as MI and ST tend to increase with this strategy, albeit at a lower incidence and effect size compared to the bleeding reduction1718. Following these RCT results, international guidelines have shifted their recommendations from one full year of TAT to a personalised, risk-guided approach, with the aspirin duration limited to hospital admission for most patients and up to one month in high ischaemic risk patients9. Reliable and contemporary real-world data are required to further support the current default strategy of DAT as recommended by European and American guidelines919.

Within this context, the prospective, international, multicentre WOEST 2 registry was conducted to obtain real-world data on prescription trends, thrombotic outcomes, and bleeding complications, with dual or triple antithrombotic therapy after PCI in patients with an indication for OAC.

Methods

Study population

The “What is the Optimal antiplatElet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation undergoing revasculariSaTion 2” (WOEST 2) registry is an international, multicentre, prospective, non-interventional cohort study designed to evaluate the use, safety and efficacy of the combined use of OAC and antiplatelet drugs after PCI in a real-world population (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02635230). The study was performed in 10 academic and non-academic PCI centres in the Netherlands and Belgium. Patients were included from 2014 to 2021.

Adult patients who underwent successful PCI with an indication for long-term OAC use (vitamin K antagonist [VKA] or non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant [NOAC]) for AF or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis were eligible for inclusion. Patients with both elective PCI and those undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were included. Patients with a new indication for OAC (e.g., AF de novo) were eligible for inclusion when OAC was started within 72 hours after PCI. Patients with a life expectancy of less than one year or a contraindication for P2Y12 inhibitor use were not included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Subject data regarding demographics, comorbidities, PCI procedure, and antithrombotic therapy were collected and directly entered into an online case report form (REDCap20). Follow-up data were collected at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months by medical file review and/or telephone interview. The data were stored, handled and secured according to national and local safety regulations. The study was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Treatment groups

Patients were classified as receiving DAT if their discharge medication consisted of a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) and OAC (acenocoumarol, phenprocoumon, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban), without aspirin. Patients were classified as receiving TAT if their discharge medication consisted of a P2Y12 inhibitor, OAC, and aspirin.

All decisions regarding the choice and duration of antithrombotic therapy after PCI were solely up to the treating physician.

Outcomes

The primary safety endpoint was clinically relevant bleeding defined as type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria21. The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), containing all-cause mortality, MI, definite ST, ischaemic stroke, and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). Secondary endpoints included major bleeding (BARC type 3 or 5), a composite of MI and ST, and the separate components of the primary safety and efficacy endpoints. All outcomes were independently adjudicated.

Statistical analysis

For this analysis, all outcomes were assessed from discharge to one-year post-discharge. In-hospital bleedings were not included in this analysis since the treatment groups were defined at discharge and recommended in-hospital treatment contained aspirin for both groups. Data for patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the time of their last known status.

To examine temporal trends in antithrombotic strategy, the proportion of patients prescribed DAT or TAT by year of procedure was tested for trend using the Cochran-Armitage test. We then examined the proportion of patients prescribed DAT or TAT across the different study centres. Baseline characteristics of patients who were prescribed DAT or TAT were compared using descriptive statistics.

The time from discharge to the first occurrence of the primary endpoints was analysed using Cox proportional hazards models with the treatment group as covariate to obtain a point estimate of the hazard ratio (HR) with a 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI). Unadjusted cumulative event rates were estimated at 365 days post-discharge and visualised in a Kaplan-Meier plot. P-values were calculated using the 2-sided log-rank test. A landmark analysis at 30 days was performed to evaluate differences in outcomes during the true aspirin treatment in the TAT arm.

Given the observational nature of the study, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models and propensity matching to account for clinical differences causing potential confounding bias between patients receiving DAT or TAT. Based on contemporary literature, the following patient characteristics were considered as potential confounders: age, sex, body mass index, CHA2DS2-VASc, HAS-BLED, indication for PCI (elective, unstable angina, non-STEMI, or STEMI), medical history of AF, mechanical heart valve prosthesis, MI, congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, clinically relevant bleeding, or discharge on potent P2Y12 inhibitors (ticagrelor or prasugrel). Cases with missing values for potential confounders were left out of the adjusted analyses. To prevent the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models from overfitting, backward stepwise selection was used. Only confounders that contributed statistical significance to the model were retained in the models to obtain the adjusted point estimates. The propensity score consisted of all the above-mentioned potential confounders. Patients on DAT were matched to patients on TAT in a 1:1 ratio, using exact matching for the indication of PCI within nearest neighbour matching, with calliper 0.25 and random matching order. The quality of the propensity model was evaluated by obtaining the C-statistic of the propensity score in the entire and matched dataset, in which a C-statistic of 0.5 in the matched dataset would represent perfect matching for the entered confounders.

Analyses for the subgroups were performed for the primary outcomes with time-to-first event with the use of the Cox proportional hazards model to evaluate treatment by subgroup interaction.

P-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.6.3 and RStudio 1.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing), utilising the packages survival and MatchIt for survival analysis and propensity score matching.

Results

Study population and prescription patterns

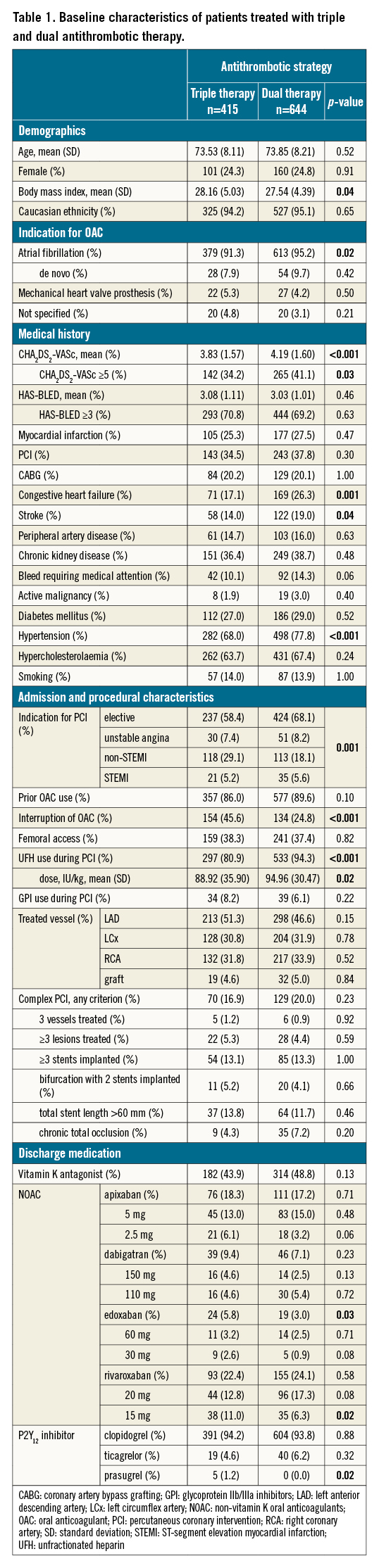

Between 2014 and 2021, a total of 1,075 patients were included in the WOEST 2 registry. After exclusion of 17 patients who were not treated with either DAT or TAT at discharge, a total of 1,058 patients from 10 centres in the Netherlands and Belgium were analysed. At 1 year, 10 patients were lost to follow-up. Baseline characteristics according to treatment are summarised in Table 1.

The mean age in this cohort was 74 (standard deviation [SD] 8) years and 24.4% were female. About one third (34.7%) of the patients underwent PCI in the setting of ACS. Of the included patients, 87.7% reported prior OAC use.

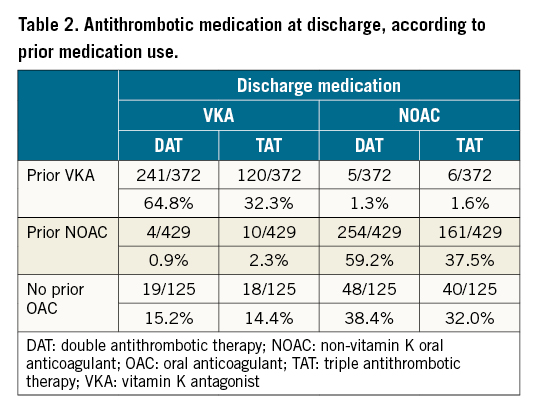

In 46.9% of the patients, a VKA was prescribed at discharge. In patients receiving NOAC (53.1%), rivaroxaban was the most frequently prescribed, followed by apixaban, dabigatran and edoxaban (43.8%, 33.3%, 15.3%, and 7.7%, respectively). Patients with prior OAC use were seldomly switched from VKA to NOAC or vice versa at the time of PCI (2.9% and 3.2%, respectively) (Table 2). Patients who were OAC naïve more often received NOAC than VKA (70.4% vs 29.6%).

The indication for OAC use at discharge was mainly driven by atrial fibrillation (93.6%), and in 4.7% the OAC use was for a mechanical heart valve prosthesis. Of the patients with AF without a mechanical heart valve prosthesis, 44.7% were prescribed VKA and 55.3% NOAC. In patients with a mechanical heart valve prosthesis, 98.0% were prescribed VKA, and one patient (2.0%) received NOAC.

At discharge, DAT was prescribed in 644 patients (60.9%) and TAT in 414 patients (39.1%). Median aspirin duration with TAT was 30 days (interquartile range [IQR] 29-57 days). In the majority of patients (93.6%), clopidogrel was the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. The prescription of DAT differed widely between study sites, varying from 7.4% DAT and 92.6% TAT to 85.7% DAT and 14.3% TAT (Supplementary Table 1). A significant temporal trend towards increased DAT prescription and decreased TAT prescription was found from 2014 through 2021 (Cochran-Armitage ptrend<0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

Patient characteristics with dual and triple antithrombotic therapy

Patients receiving DAT tended to have more comorbidities as compared to patients receiving TAT, including a history of hypertension (77.8% vs 67.9%), previous stroke (19.0% vs 14.0%), congestive heart failure (26.3% vs 17.1%) and atrial fibrillation (95.2% vs 91.3%; p<0.05 for all). In line with this, the thrombotic risk predicted by the CHA2DS2-VASc score was significantly higher in patients treated with DAT than with TAT (score ≥5 in 41% vs 34% of patients; p=0.03). Patients treated with TAT, on the other hand, had a higher body mass index (28.1 vs 27.5; p=0.04), and were more likely to have had PCI for ACS instead of elective PCI (41.6% vs 31.9%; p<0.01). The risk of bleeding predicted by the HAS-BLED score did not differ between the groups, although patients prescribed DAT were slightly more likely to have had a history of bleeding (14.3% vs 10.1%; p=0.06). There were no meaningful differences in other baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Outcomes with dual and triple therapy

The use of DAT after discharge was associated with a significant decrease of 6.6% in clinically relevant bleeding (BARC type 2, 3, or 5) at 1 year, compared to patients treated with TAT (16.8% vs 23.6%; p=0.003) (Central illustration A). However, no significant differences were found in major bleeding (7.6% vs 7.7%; p=0.97) (Central illustration B) or haemorrhagic stroke (0.3% vs 0.7%; p=0.35) (Table 2). The use of DAT was associated with a numerically higher rate of MACCE (12.4% vs 9.6%; p=0.17) (Central illustration C). The numerical increase of 2.8% in MACCE with DAT compared to TAT consisted of myocardial infarction (5.0% vs 4.3%) (Central illustration D), stent thrombosis (1.7% vs 1.0%), and all-cause death (6.2% vs 5.8%); however, statistical significance between DAT and TAT for any of the separate endpoints was not reached.

Central illustration. Incidence curves of outcomes with double or triple antithrombotic therapy. A) Outcomes for clinically relevant bleeding; B) major bleeding; C) major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; and D) myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium classification

Landmark analysis at 30 days showed no statistically significant differences in outcomes beyond this time point (Supplementary Figure 1).

Adjusted outcome analysis

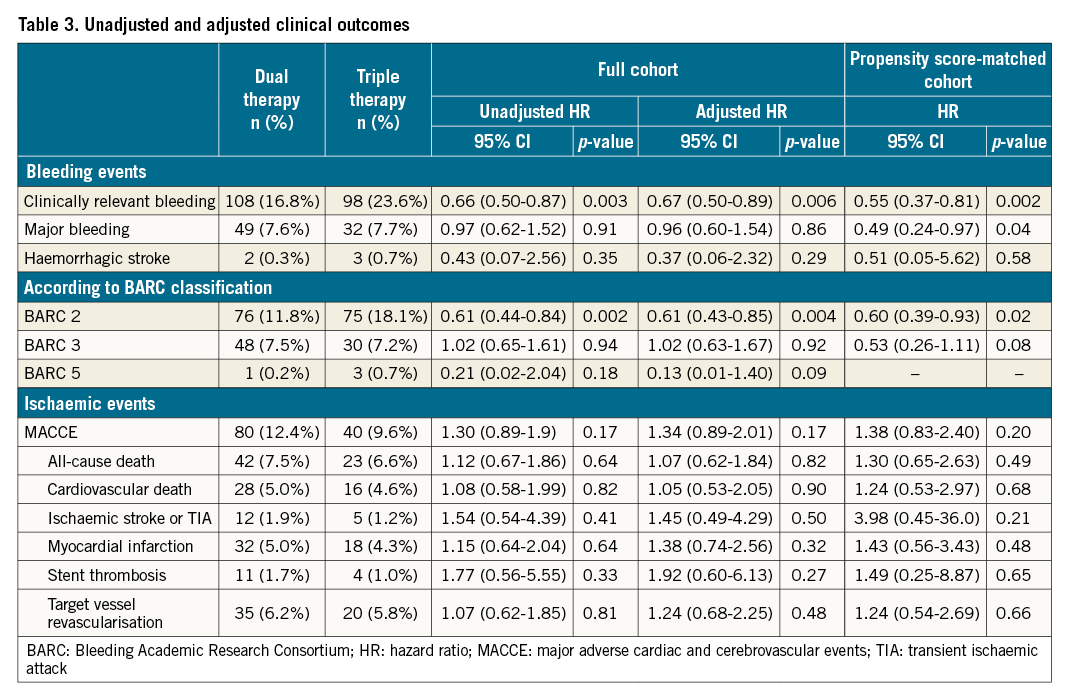

Unadjusted and adjusted outcomes by multivariable Cox regression and propensity score matching are summarised in Table 3.

After multivariate adjusted Cox regression, clinically relevant bleeding remained significantly decreased with DAT as compared to TAT (HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.50-0.89), while major bleeding remained similar (HR 0.96 95% CI: 0.60-1.54). Neither MACCE (HR 1.34 95% CI: 0.89-2.01) nor any of its separate components showed a significant association with TAT or DAT (all-cause death: HR 1.07, 95% CI: 0.62-1.84; MI: HR 1.38, 95% CI: 0.74-2.56; ST: HR 1.92, 95% CI: 0.60-6.13).

The propensity score showed near-perfect matching with a C-statistic decreasing from 0.63 in the unmatched cohort to 0.51 in the matched cohort. The matched cohort consisted of 302/519 patients treated with DAT matched to 302/321 patients on TAT. Its baseline characteristics are summarised in Supplementary Table 3. After propensity score matching, clinically relevant bleeding remained significantly decreased with DAT (HR 0.55, 95% CI: 0.37-0.81). In contrast to the unadjusted and multivariate Cox regression analyses, major bleeding was reduced with DAT in the propensity score-matched cohort. There was no significant difference in MACCE between the groups (HR 1.38, 95% CI: 0.83-2.40). The separate components of all-cause death (HR 1.30, 95% CI: 0.65-2.63), MI (HR 1.43, 95% CI: 0.56-3.43), and ST (HR 1.49, 95% CI: 0.25-8.87) remained indifferent as well.

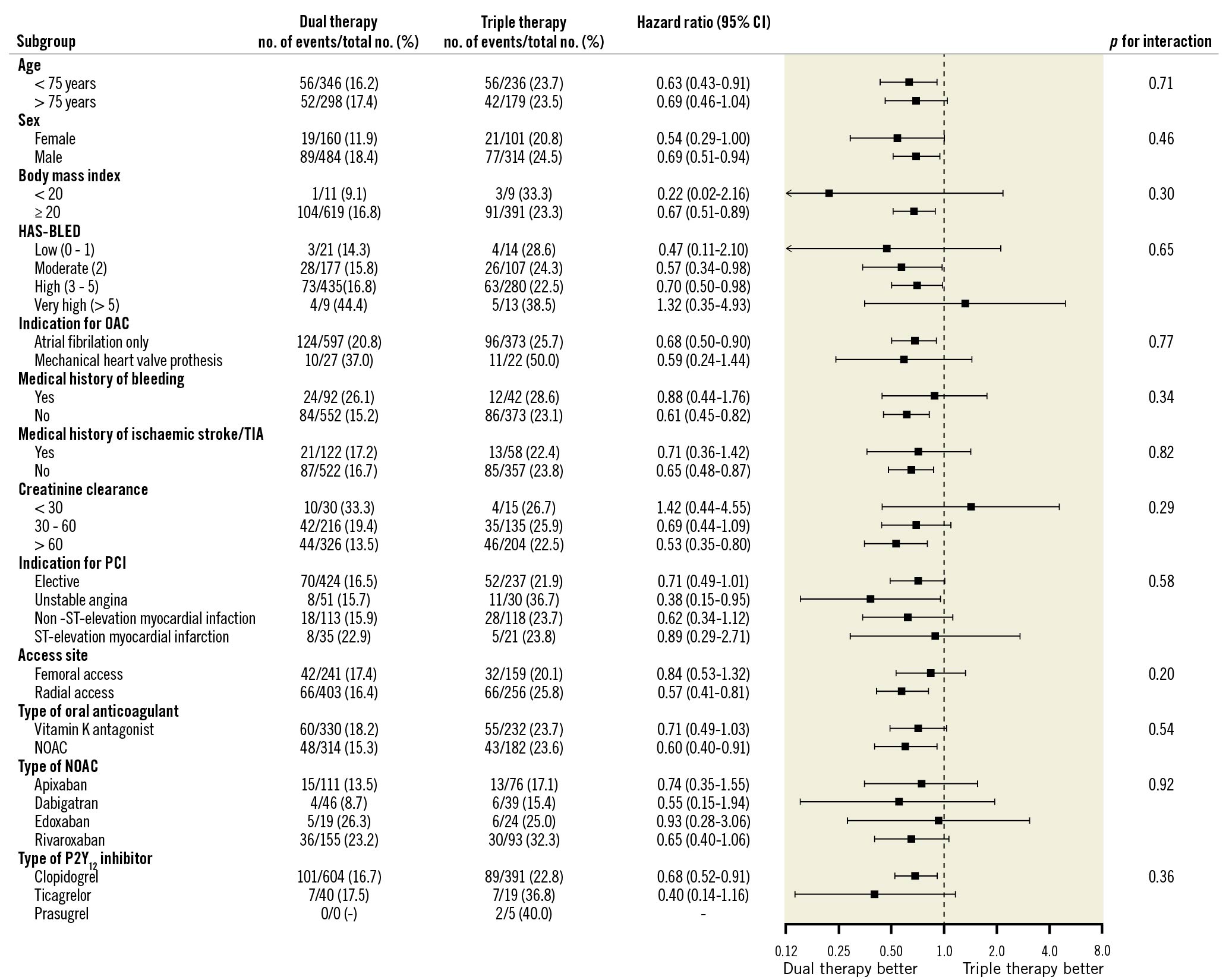

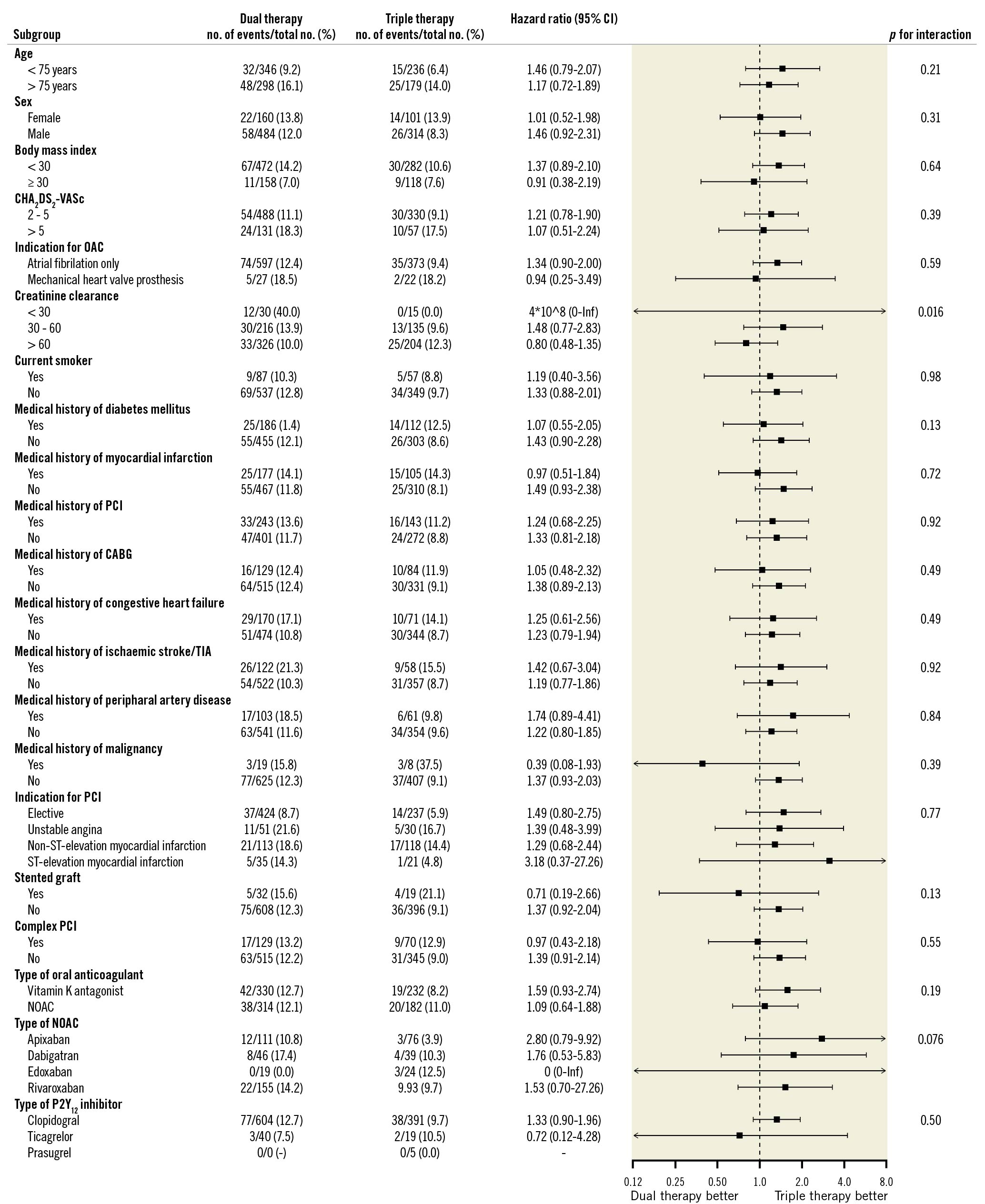

Subgroup analyses

Analyses of the primary endpoints were performed in several subgroups (mentioned in the methods section) at risk of bleeding or thrombosis. The results were generally consistent with those in the whole cohort (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Subgroup analyses for clinically relevant bleeding. NOAC: non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant; OAC: oral anticoagulant; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Figure 2. Subgroup analyses for major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; NOAC: non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant; OAC: oral anticoagulant; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Especially, for ACS patients, a similar decrease in bleeding (HR 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38-0.94) and no increase of MACCE (HR 1.4, 95% CI: 0.83-2.4) and MI (HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.44-1.9) or ST (HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.21-3.4) was seen with the use of DAT compared to TAT. Even so, separately evaluating patients with AF, thus leaving out patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses, decreased bleeding (HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.50-0.90) and no increase of MACCE (HR 1.34, 95% CI: 0.90-2.00) and MI (HR 1.5, 95% CI: 0.76-2.8) or ST (HR 2.3, 95% CI: 0.64-8.2) was found. Similarly, for patients with a mechanical heart valve prosthesis, a non-significant decrease in bleeding (HR 0.59, 95 CI: 0.24-1.44) and no increase of MACCE (HR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.25-3.49) and MI (HR 0.19, 95% CI: 0.02-1.7) or ischaemic stroke or TIA (HR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.05-12) was seen.

Discussion

In this analysis of the WOEST 2 registry in patients with OAC undergoing PCI between 2014 and 2021, we found that there was a wide variety in prescription of DAT and TAT across centres, with an increased preference for DAT over the years. In our primary, unadjusted analysis at one year post-discharge, we found that dual antithrombotic therapy was associated with significantly less clinically relevant post-discharge bleeding complications without a statistically significant increase in MACCE. We conclude that major bleeding seemed not to differ between patients treated with DAT or TAT since only the propensity score-matched analysis but not the unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression analysis showed a difference. Thus the difference between the two groups was primarily driven by BARC type 2 bleeding. These results were also consistent for patients with complex PCI or high bleeding risk, as shown in the subgroup analyses. These findings support the clinical benefit of DAT as a strategy to prevent bleeding complications without an apparent increase of thrombotic events such as myocardial infarction for most patients on OAC undergoing PCI. It also indicates that high-risk patients may be adequately identified and accordingly treated.

Comparison to existing literature

Both ischaemic events and bleeding complications in patients using antithrombotic therapy after PCI are strongly associated with adverse outcomes8. In the past decade, several RCTs have focused on the safety and efficacy of DAT and TAT in patients with oral anticoagulants undergoing PCI, with the primary aim to reduce bleeding complications of antithrombotic therapy. The WOEST11, PIONEER AF-PCI12, RE-DUAL PCI1314, AUGUSTUS15, and ENTRUST-AF PCI16 trials found reduced bleeding risk with DAT as compared to TAT, with generally no differences in MACCE. However, none of these trials were completed with statistical power to detect differences in MACCE, whilst meta-analyses of these trials found increased risk of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis1718. Nonetheless, international guidelines and consensus papers have shifted their recommendations over the years during this registry, towards an approach of post-discharge DAT for its clear benefit with regards to bleeding complications, with TAT reserved for those patients with high thrombotic risk and favourable bleeding risk91922. Still, in a recent survey, the majority of interventional cardiologists indicated that they would prescribe TAT to a PCI patient discharged on OAC23. Thus, prospective real-world studies with reliable and high-quality data on this subject, like the present study, might be needed to convince medical specialists of the efficacy of DAT.

Our study adds to the literature, providing a prospective registry with reliable insight in real-world data of a heterogeneous, contemporary cohort of patients treated with DAT or TAT. Two other prospective real-world cohorts comparing the safety and efficacy of DAT and TAT in patients with AF undergoing PCI, the MUSICA24 and AFCAS25 studies, included patients before the randomised controlled trials of DAT vs TAT were published. They found only 8-11% of patients were treated with DAT and 69-74% with TAT, the remainder being treated with dual antiplatelet therapy. In contrast to the results of this present study and the aforementioned RCTs, the AFCAS registry found no statistical difference in bleeding outcomes between DAT and TAT, whereas the MUSICA study found less minor bleeding with DAT as compared to TAT. Ischaemic outcomes did not differ between the groups in either study. Also, more recently, numerous retrospective cohort studies, including large nationwide registries62627, generally found a decreased risk of bleeding with DAT, without significant differences in thrombotic outcomes. This is in line with our observations. As the current study prospectively enrolled patients in a contemporary cohort, the portion of patients receiving DAT was much higher (60.9%). In our view, this allowed for a better estimation of (un-)adjusted bleeding and thrombotic outcomes in relation to antithrombotic regimen.

The RCTs on DAT and TAT included a predominantly (around 75%) male study population. Also, patients with indications for OAC other than AF were excluded in most RCTs, except for the WOEST trial. Patients with severe renal insufficiency were also not included. The observational nature of this study, without stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, allowed us to report on a broader patient population. Our study confirms the imbalance of sexes in this population, which has also been found in other recent real-world cohorts28. We also found consistent results within the whole cohort amongst patients with a mechanical heart valve prosthesis. In all major RCTs on this subject, patients with AF and a mechanical heart valve were excluded12131516.

Limitations

Some limitations have to be addressed for this study. First, inherent to the design and goals of the study, the study was non-randomised. Still, we believe the results of our observational cohort are convincing, given the all-comers design of the study and the in-depth description of baseline and procedural characteristics. Moreover, the consistency of the study results in multivariable Cox regression, propensity score matching with exact matching for PCI indication, and extensive subgroup analyses showed consistent results. Second, due to slow enrolment, the study was underpowered to draw conclusions for thrombotic outcomes. However, we found similar effect sizes in meta-analyses of the trials1617, which might support the reliability of our results. For example, in the meta-analyses, a significant increase of MI and ST was found with point estimates for HR of 1.2 and 1.5, respectively. Our study found similar point estimates for the HR: 1.1 and 1.8, respectively; however these were non-significant due to the smaller sample size. Third, we did not record the motivation of the cardiologist to prescribe DAT or TAT. This is mostly covered by recording patient characteristics including risk scores; however, we cannot fully explain why patients with a high CHA2DS2-VASc score were more likely to receive DAT, whereas HAS-BLED did not differ between groups. Despite this appearance of not being guided by risk scores, cardiologists seem to have chosen the right regimen as no significant differences in thrombotic outcomes were found. Also, this could be another example of the treatment-risk paradox in which patients at the highest risk tend to be treated less intensively29. Finally, since patients using (N)OAC for pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, or intracardiac thrombus were not included (unless AF or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis was present), we cannot generalise this result to those populations.

Future perspectives

Over the past decades, the antithrombotic treatment after PCI in patients with an indication for (N)OAC has improved vastly by limiting aspirin duration from 1 year to a maximum of one month, which reduces bleeding risk. During the first month, some benefit may still be obtained from intensified antithrombotic treatment30. It may be reasonable to select high-risk patients eligible for initial TAT by a recently proposed risk score, based on clinical parameters including extent of vascular and coronary disease, platelet count, left ventricular ejection fraction, and renal function14. Since TAT is accompanied by an unacceptable high bleeding risk for most patients, current studies are focusing on alternative antithrombotic strategies to optimise treatment for this population. The ZON-HR RE-DUAL PCI trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04688723) investigates DAT with ticagrelor as a more potent option compared to DAT with clopidogrel. The WOEST 3 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04436978) will compare dual antiplatelet therapy without OAC in the first month after ACS or PCI to standard therapy consisting of NOAC and P2Y12 inhibitor, with aspirin only limited to high-risk cases. Also, genetic testing to select the most effective P2Y12 inhibitor may be a reasonable option31; however it has not yet been studied in this population32.

Conclusions

Our prospective real-world cohort study comparing DAT to TAT in patients with AF or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis undergoing PCI, found a substantially lower risk of clinically relevant bleeding without a statistically significant penalty in ischaemic events. Major bleeding did not significantly differ between the groups.

Impact on daily practice

Our large prospective real-world cohort study comparing DAT to TAT in patients with AF or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis undergoing PCI found a substantially lower risk of clinically relevant bleeding without a significant penalty in ischaemic events. These results should support clinicians to further increase the utilisation of DAT post-discharge, and to limit the use of TAT only to those at very high ischaemic risk and with limited bleeding risk.

Funding

This research was made possible by financial support of the St. Antonius Hospital Research Fund.

Conflict of interest statement

W. Dewilde reports speaker fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer and Terumo. A. de Veer reports personal fees from Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim. R.H. Olie reports honoraria for presentations and educational events from Leo Pharma and Portola/Alexion. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.